Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 12

Flavone & monohydroxy flavones on paclitaxel - induced peripheral neuropathy in mice: A prospective Oncotherapeutic study

Parimala Kathirvelu1, Nithya Panneerselvam2*, Vijaykumar Sayeli3, Jagan Nadipelly4, Jaikumar Shanmugasundaram5 and Viswanathan Subramanian62Department of Pharmacology, Sri Lalithambigai Medical College and Hospital, Dr. MGR Educational and Research Institute, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India, Meenakshi Academy of Higher Edu, India

3Department of Pharmacology, Mamata Medical College, Khammam, Telangana, India

4Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, Texila American University, Georgetown, Guyana

5Department of Pharmacology, Panimalar Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6Department of Pharmacology, Meenakshi Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Meenakshi Academy of Higher Education and Research, Deemed to be University, Chennai, Tamil, India

Nithya Panneerselvam, Department of Pharmacology, Sri Lalithambigai Medical College and Hospital, Dr. MGR Educational and Research Institute, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India, Meenakshi Academy of Higher Edu, India, Email: nithyapanneerselvam83@gmail.com

Received: 24-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-178027; , Pre QC No. OAR-25-178027 (PQ); Editor assigned: 26-Nov-2025, Pre QC No. OAR-25-178027 (PQ); Reviewed: 10-Dec-2025, QC No. OAR-25-178027; Revised: 19-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-178027 (R); Published: 29-Dec-2025

Abstract

Background: Flavonoids are naturally occurring compounds known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. This study examined whether flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives could reduce peripheral neuropathy caused by paclitaxel, a widely used anticancer drug.

Methods: Male Swiss albino mice were treated with flavone or monohydroxyflavones at doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg. Neuropathic symptoms were evaluated using standard behavioural tests: von Frey filaments for mechanical sensitivity, the acetone test for cold response and the tail-immersion method for thermal pain.

Results: Mice receiving paclitaxel developed clear signs of neuropathy. Treatment with flavones and their derivatives reduced these symptoms in a dose-dependent manner. Among the compounds tested, 5-hydroxyflavone produced the most potent effect, followed by 6-hydroxyflavone, flavone and 7-hydroxyflavone. The protective effect appeared to involve several neural pathways, including opioid, GABAergic, serotonergic, adrenergic and K+-ATP channel systems. The compounds also helped prevent structural damage to the sciatic nerve.

Conclusion: Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives showed meaningful protection against paclitaxel-induced neuropathy in mice. Their multi-pathway action and ability to limit nerve damage suggest that these molecules serve as valuable leads for developing treatments for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Keywords

Paclitaxel; Peripheral neuropathy; Mice; Flavones; Anti-neuropathic effect

Introduction

Paclitaxel is a broad-spectrum antineoplastic drug obtained from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). It's routinely used to treat several solid tumors, including cancers of the ovary, breast, lung and head and neck. However, its clinical use is limited by the frequent occurrence of peripheral neuropathy. Symptoms often begin within 24–72 hours even after a single dose, affecting nearly 59–78% of patients, includes numbness, tingling, paresthesia and burning pain in a characteristic glove-and-stocking pattern [1]. While mild may resolve within months after discontinuation of therapy, individuals who develop more severe forms may experience long-lasting symptoms [2].

Currently, duloxetine, pregabalin, gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants are recommended as first-line pharmacological options for neuropathic pain caused by chemotherapeutic agents [3]. Experimental work has also shown that biological agents, such as nerve growth factor and IGF-1, have therapeutic potential to treat paclitaxel-induced neuropathy [4]. Progress in developing more effective therapies for CIPN has been slow, mainly due to limited clarity regarding its underlying mechanisms. Proposed contributors include oxidative injury to mitochondria, impaired function of neuronal ion channels and activation of inflammatory pathways involving glial cells [1].

Considering these mechanisms, compounds that counter oxidative stress, modulate ion-channel activity or reduce neuroinflammation may offer benefit. Flavones represent one such group well known for antioxidant and free-radical-scavenging properties [5] and numerous flavone derivatives have shown antinociceptive and antiinflammatory activity in preclinical studies [6–9]. Their beneficial effects appear to involve modulation of neuronal pathways, regulation of ion channels and attenuation of inflammatory mediators—mechanisms that closely align with the proposed pathophysiology of CIPN. Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives have previously demonstrated significant antinociceptive effects in mice [10] and anti-inflammatory activity of various rat models [11].

Based on this background, the present study evaluated the potential of flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives (5-OHF, 6-OHF and 7-OHF) in reducing paclitaxel-induced CIPN in mice. Evidence indicates that even a single dose of paclitaxel can produce neuropathic symptoms such as thermal hyperalgesia, mechanical allodynia and cold allodynia [12]. Since flavones engage multiple neuronal mechanisms associated with pain modulation, the study investigated both behavioural outcomes and the possible involvement of these pathways in their protective effects. Additionally, paclitaxel is known to cause dose-dependent degenerative changes in peripheral nerves [13–14], prompting further investigation into whether flavone derivatives could mitigate these structural alterations in the sciatic nerve.

Materials and Methods

Swiss albino mice of the male gender, weighing 20-25 g, were selected. The animals were housed in groups of six under controlled temperature conditions (21–24°C), with free access to food and water and maintained on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. This was done to have uniformity throughout the experiments for the study and to prevent any circadian changes. Each group consisted of six animals in all the experimental studies, which were randomly selected. Each animal was used only once. The study was approved by IEC (KN/COL/3408/2014 and 002/2015 dated 22.7.2014 and 24.6.2015) and experimental procedures were performed as per the Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA), India Guidelines and the National Research Council's guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Drugs and chemicals

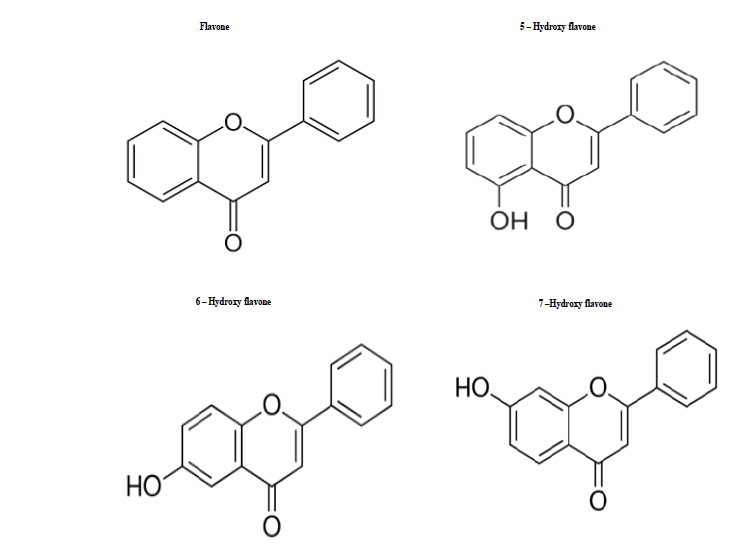

The compounds used in this work (Figure 1) included flavone, monohydroxy (5, 6 and 7) sourced from Research Organics, Chennai, India. Additional agents were paclitaxel (Intas, India), morphine sulphate (Pharma Chemico Laboratories, India), naloxone hydrochloride (Endo Labs, USA), yohimbine hydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co., USA), glibenclamide (Dr. Reddy's Laboratory, India), bicuculline methiodide (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., Japan) and ondansetron (Sunvet Healthcare, India).

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of investigated flavones.

Drug preparation

Flavone and its derivatives were prepared as a fine suspension in 0.5% CMC (Carboxymethyl Cellulose; Merck Laboratories) and administered subcutaneously to the experimental animals. Paclitaxel was diluted in physiological saline and given intraperitoneally to the mice. Morphine sulphate (injection) was diluted in distilled water and administered subcutaneously.

Paclitaxel-induced neuropathy

Mice received intraperitoneal dose of paclitaxel (10 mg/kg) in saline on day 1. Twenty-four hours later, the animals were assessed for neuropathic changes [12]. Animals were then administered 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg of the study compounds (Flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF), 10 mg/kg morphine or 0.5% CMC (vehicle) subcutaneously. After 30 minutes, the mice were re-evaluated using the same behavioural tests.

Evaluation of mechanical allodynia

A plastic cage measuring 13 cm (7 × 7 cm) with a wire-mesh floor was used for each mouse. Each hind paw's plantar surface was stimulated with a 0.69 mN von Frey filament, placed perpendicularly and maintained for 1-3 seconds until a minor bend formed [15] following a 15-minute acclimatisation period. Each hind paw received five stimulations using a von Frey aesthesiometer and graded as ‘0’ (no response), ‘1’ (paw withdrawal) and ‘2’ (licking or flinching). Every stimulus was administered every 30 seconds. The final value was calculated by adding the scores from each of the ten stimulations.

Evaluation of cold allodynia

The presence of cold allodynia was assessed using an acetoneevaporation assay. A small drop of acetone was applied to the plantar surface of the hind paw and the subsequent paw withdrawal response was quantified [16]. The behavioral response was observed for 20 seconds and scored using the following 4-point scale: 0: No response; 1: Immediate paw withdrawal; 2: Prolonged withdrawal or flicking; 3: Vigorous licking or biting of the paw.

Each paw tested alternately with an interval of 1-minute between applications. The cumulative score from all six trials (three per paw) was used as the final measurement of cold allodynia.

Thermal hyperalgesia

Assessed using a tail immersion test in hot water [17]. The mouse was kept restrained in its holder and its tail up to a mark of 1cm from its base was plunged in a thermostatically-controlled water bath set at the temperature of 48.0 ± 0.5ºC. The reaction time was defined as the time taken for the mouse to flick its tail out of the hot water and recorded before and 30 minutes after treatment. A significant increase in the mean reaction time before and after drug treatment indicates reduced pain sensitivity to a heat stimulus. To prevent thermal injury to the tail, a 20-second cut-off time was maintained. Maximum Protective Effect (MPE %) was calculated as =Test latency-Control latency/Cut off time–Control latency × 100

Investigation on the mode of action of flavone and monohydroxy flavones

Flavone compounds have been shown to engage multiple neuronal mechanisms in mediating their antinociceptive effects. Hence, it was of interest to investigate whether neuronal mechanisms are involved in the action of flavones in attenuating neuropathy. Paclitaxel was administered to mice to establish a model of neuropathic pain. Neuropathic manifestations were evaluated after 24 h of paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment. The effects of flavone and mono-hydroxy flavones (5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF) on the expression of different neuropathic manifestations, including mechanical and cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, were investigated using the methods described earlier. Different flavone compounds were employed in a dose of 200 mg/kg, s.c.

To investigate the process involved in the actions of flavones, the following interacting drugs were administered 15 min before the flavones treatment. • Naloxone, intraperitoneal 5 mg/kg (Opioid) • Yohimbine, intraperitoneal 1mg/kg (Adrenergic) • Ondansetron, intraperitoneal 0.1 mg/kg (Serotonergic) • Bicuculline, intraperitoneal 1mg/kg (GABAergic) • Glibenclamide, intraperitoneal 10 mg/kg (K+ATP channel) The neuropathic manifestations were recorded before and 30 minutes after flavone treatment.

Neuronal changes

Flavone and monohydroxy flavones (5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF) were administered consecutively for seven days in a dose of 200 mg/kg subcutaneously to different groups of mice. 10 mg/kg of Paclitaxel was given to these mice i.p. on three alternate days (Days 2, 4 and 6).

The animals were exposed to excess CO2, sciatic nerves were harvested and fixed in 10% buffered formalin [18]. Sections were made (5 μm thickness) and stained with H and E (Haematoxylin and Eosin) or TB (Toluidine Blue). The sections were visualized under light microscopy to detect any histological changes.

Statistical analysis

Collected data were analyzed using ANOVA for multiple comparisons following Dunnett's t-test for/paired t-test. SPSS v. 16 was used for statistical analysis. Data were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Mechanical allodynia

While aesthesiometer was placed on the mice's hind paw (plantar surface), an immediate withdrawal response was observed, which was graded and scored across different treatments. Treatment with the vehicle did not alter the paw-withdrawal response score. Morphine treatment completely suppressed the paw withdrawal response score (Table 1).

Only the 200 mg/kg dose of Flavone, 6-OHF and 7-OHF treatments produced a statistically significant reduction in the score. However, 5-OHF showed a substantial decrease in response at both 100 and 200 mg/kg (Table 1).

| Dose mg/kg sc | Pre flavone administration | Post flavone administration | Pre 5-OHF administration | Post 5-OHF administration | Pre 6-OHF administration | Post 6-OHF administration | Pre 7-OHF administration | Post 7-OHF administration |

| 50 | 18.33 ± 1.36 | 16.66 ± 1.96 | 19.33 ± 0.42 | 17.83 ± 1.97 | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 17.00 ± 1.52 | 18.83 ± 0.47 | 18.83 ± 0.65 |

| 100 | 16.66 ± 1.96 | 16.33 ± 1.74 | 16.00 ± 2.52 | 12.33 ± 1.68* | 19.16 ± 0.54 | 18.00 ± 0.89 | 18.16 ± 0.65 | 15.33 ± 1.96 |

| 200 | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 1.66 | 12.50 ± 2.10* | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 2.16* | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* |

| Note: The paw withdrawal score in mice treated with vehicle were 19.16 ± 0.54 and 19.16 ± 0.54 pre and post treatment. The paw withdrawal response score in morphine 10mg/kg sc treated mice were 18.83±0.65 and 18.83±0.65 pre and post treatment Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (Paired ‘t’ test) @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 hours prior to the test. Mechanical allodynia determined before and 30 minutes after vehicle/morphine/flavone and mono hydroxy flavones treatment on the next day. |

||||||||

Tab. 1. Effectiveness of flavone and monohydroxy flavones in mechanical allodynia of paclitaxel pretreated mice.

Cold allodynia

Acetone bubble application to the hind paw of paclitaxel-treated mice elicited an aversive behavioral response, including immediate flinching, biting or paw withdrawal. Treatment with the vehicle did not alter the score. Treatment with the morphine drug produced a significant decrease in the score compared to the score noted before drug treatment. Flavone, OHF, 6-OHF and 7-OHF provided effective relief from neuropathic pain. Treated animals showed a significantly dulled pain response, tolerating uncomfortable sensations for more extended periods than their untreated counterparts at doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg, compared with their pretreatment values (Table 2).

| Paw withdrawal response scores after various treatments in mice | ||||||||

| Dose mg/kg sc | Pre flavone administration | Post flavone administration | Pre 5-OHF administration | Post 5-OHF administration | Pre 6-OHF administration | Post 6-OHF administration | Pre 7-OHF administration | Post 7-OHF administration |

| 50 | 17.33 ± 0.33 | 16.66 ± 1.33 | 14.66 ± 1.30 | 12.00 ± 0.93 | 14.50 ± 0.76 | 14.00 ± 1.21 | 16.16 ± 0.60 | 14.50 ± 1.11 |

| 100 | 16.66 ± 0.42 | 11.33 ± 1.66* | 16.16 ± 1.13 | 10.66 ± 1.30* | 16.33 ± 0.66 | 10.83 ± 0.90* | 15.16 ± 0.90 | 11.50 ± 1.23* |

| 200 | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 13.50 ± 0.76 | 8.66 ± 0.84* | 15.66 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43* | 15.24 ± 0.61 | 11.50 ± 1.62* |

| Note: The paw withdrawal response score in vehicle treated mice were 17.66 ± 0.21 and 17.50 ± 0.22 pre and post treatment. The paw withdrawal response score in morphine 10mg/kg sc treated mice were 18.00 ± 0.00 and 0.50 ± 0.22* pre and post treatment. Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (Paired ‘t’ test) @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 hours prior to the test. Cold allodynia was determined before and 30 minutes after vehicle/morphine/flavone and mono hydroxy flavones treatment on the next day. |

||||||||

Tab. 2. Effectiveness of flavone and mono hydroxy flavones in cold allodynia of paclitaxel pretreated mice.

Thermal hyperalgesia

In animals undergoing treatment with paclitaxel, thermal hyperalgesia was analysed after administration of the flavone compounds or morphine. The maximum protective effect (MPE) for various doses was calculated and the mean reaction time (17.61 ± 0.33s) significantly increased when treated with morphine, providing 87.89% protection against thermal hyperalgesia induced by paclitaxel. Treatment with various flavone derivatives produced a highly dose-dependent increase in the mean reaction time. 7-OHF (200 mg/kg) produced nearly 24% MPE, Flavone 36%, 5-OHF 39% and 6-OHF produced a maximum of 45% MPE (Table 3).

| Mean increase in reaction time for tail withdrawal in mice (secs) | ||||

| Dose mg/kg s.c | Flavone | 5-OHF | 6-OHF | 7-OHF |

| 50 | 2.25 ± 0.65 | 3.20 ± 1.32 | 2.12 ± 0.69 | 2.42 ± 0.54 |

| 100 | 2.52 ± 0.40 | 4.18 ± 1.28 | 8.13 ± 1.38* | 3.45 ± 0.63* |

| 200 | 7.45 ± 0.63* | 7.92 ± 1.65* | 9.06 ± 1.60* | 5.05 ± 0.28* |

| Note: Mean reaction time in vehicle and morphine (10mg/kg sc) treated mice were 0.26 ± 0.62 and 17.61 ± 0.33 respectively IEach value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 hours prior to the test. Thermal hyperalgesia was determined before and 30 minutes after vehicle/morphine/flavone and mono hydroxy flavones treatment on the next day. |

||||

Tab. 3. Effectiveness of flavone and monohydroxy flavones on paclitaxel induced heat hyperalge

Effect of opioid mechanism and flavone derivatives

The paw withdrawal score in paclitaxel caused mechanical and cold allodynia in mice was not affected by vehicle or naloxone treatment. The investigated flavone and monohydroxy flavones showed a significant reduction in the paclitaxel-treated mice. This decrease in paw withdrawal response score in mechanical allodynia produced by the above flavone derivatives was not observed in animals pretreated with naloxonex, as shown in Table 4.

Compared with pretreatment values, naloxone-pretreated mice, Flavone, 5-OHF or 6-OHF treatment failed to produce a significant reduction in the cold allodynia response score. However, naloxone pretreatment did not alter the response to 7-OHF treatment (Table 4).

Naloxone in the dose employed did not significantly alter the mean change in reaction time in paclitaxel-induced thermal hyperalgesia compared to vehicle treatment. Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives markedly increased the reaction time in paclitaxel-treated mice. However, in naloxone pretreated animals, the monohydroxy flavones were unable to produce an increase in reaction time. Naloxone pretreatment had not altered the effect of flavone (Table 4).

| Treatment (mg/kg) | Mechanical allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Cold allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Thermal hyperalgesia | ||

| Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Mean change in reaction time in sec | |

| Vehicle | 17.17 ± 0.83 | 15.50 ± 1.26 | 14.83 ± 1.01 | 12.67 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.59 |

| Naloxone (5) | 16.67 ± 1.82 | 17.67 ± 1.23 | 11.50 ± 1.48 | 11.17 ± 1.23 | 0.67± 0.29 |

| Flavone (200) | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 7.45 ± 0.63# |

| 5-OHF (200) | 17.50 ± 0.89 | 11.50 ± 1.50* | 16.17 ± 1.13 | 10.67 ± 1.30* | 7.86 ± 0.61# |

| 6-OHF (200) | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 1.70* | 15.67 ±0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43* | 8.99 ± 0.74# |

| 7-OHF (200) | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* | 16.83 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ± 0.89* | 4.01 ± 0.53# |

| Naloxone£ + Flavone | 18.83 ± 067 | 19.17 ± 0.54 | 10.07 ± 0.42 | 9.83 ± 1.16 | 7.18 ± 0.72 |

| Naloxone£ + 5-OHF | 19.33 ± 0.67 | 18.83 ± 0.83 | 19.33 ± 0.67 | 18.83 ± 0.83 | 0.63 ± 0.32† |

| Naloxone£ + 6-OHF | 16.50 ± 1.69 | 18.83 ± 0.98 | 15.17 ± 1.27 | 12.83 ± 1.33 | 2.01 ± 0.14† |

| Naloxone£ +7-OHF | 19.17 ± 0.54 | 18.83 ± 0.60 | 16.67 ± 0.66 | 12.50 ± 1.11* | 0.53 ± 0.13† |

| Note: Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (ANOVA, Paired ‘t’ test) #P<0.001 compared with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) † P<0.05 compared with respective flavone treatment alone @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h prior to the test. £Naloxone 5 mg/kg , was administered i.p. 15 min prior to flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF (200 mg/kg, s.c) treatment |

|||||

Tab. 4. Effect of opioid mechanism and flavone derivatives in chemotherapy-induced mechanical and cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice.

Effect of K+ATP channels and flavone derivatives

Vehicle or glibenclamide treatment did not show any highly significant changes in scores due to mechanical and cold allodynia in paclitaxel-administered animals. A drastic reduction in score was observed in flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF-treated groups compared with vehicle-treated groups. However, in glibenclamide pretreated animals, none of the Flavone and its derivatives were able to reduce the response score due to mechanical allodynia. Still, the response to cold allodynia in flavone-pretreated animals remained unaltered. 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF treatment failed to reduce cold allodynia scores (Table 5).

Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives significantly increased the mean change in reaction time in thermal hyperalgesia compared to vehicle treatment. Treatment with glibenclamide alone did not change the reaction time substantially compared to the vehicle. Glibenclamide pretreatment significantly reversed the responses of 5-OHF, 6-OHF and 7-OHF without altering the response of Flavone, as given in Table 5.

| Treatment (mg/kg) | Mechanical allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Cold allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Thermal hyperalgesia | ||

| Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Mean change in reaction time in sec | |

| Vehicle | 17.17 ± 0.83 | 15.50 ± 1.26 | 14.83 ± 1.01 | 12.67 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.59 |

| Glibenclamide (10) | 15.3 ± 1.45 | 17.67 ± 1.23 | 15.50 ± 0.76 | 13.00 ± 1.39 | -0.69 ± 0.58 |

| Flavone (200) | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 7.45 ± 0.63# |

| 5-OHF (200) | 17.50 ± 0.89 | 11.50 ± 1.50* | 16.17 ± 1.13 | 10.67 ±1.30* | 7.86 ± 0.61# |

| 6-OHF (200) | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 1.70* | 15.67 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43* | 8.99 ± 0.74# |

| 7-OHF (200) | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* | 16.83 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ± 0.89* | 4.01 ± 0.53# |

| Glibenclamide£ + Flavone | 18.33 ± 0.76 | 17.17 ± 1.3 | 12.17 ± 0.60 | 7.83 ± 0.47* | 6.97 ± 0.45 |

| Glibenclamide£ + 5-OHF | 16.50 ± 1.48 | 17.50 ± 1.77 | 15.67 ± 1.50 | 13.83 ± 1.96 | -0.13 ± 0.83† |

| Glibenclamide£ + 6-OHF | 18.00 ± 1.10 | 17.33 ± 1.90 | 13.50 ± 1.14 | 11.50 ± 1.06 | 1.57 ± 1.85† |

| Glibenclamide£ + 7-OHF | 19.67 ± 0.21 | 19.50 ± 0.34 | 15.83 ± 0.94 | 14.17 ± 1.22 | 0.91 ± 0.26† |

| Note: Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (ANOVA, Paired ‘t’ test) #P<0.001 compared with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) †P<0.05 compared with respective flavone treatment alone @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h prior to the test. £Glibenclamide 10 mg/kg, was administered i.p. 15 min prior to flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF (200 mg/kg, s.c) treatments. |

|||||

Tab. 5. Effect of K+ATP channels and flavone derivatives in paclitaxel-induced mechanical, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice.

Effect of GABAergic mechanism and flavone derivatives

Vehicle or bicuculline administration did not alter the response score due to mechanical and cold allodynia in paclitaxel-treated animals. Administration of flavone and its derivatives reduced paw withdrawal scores for mechanical and cold allodynia to a significant level compared with vehicle treatment, as shown in Table 6.

In bicuculline-pretreated animals, administration of flavone or hydroxy flavones did not show any significant alteration in the score of mechanical allodynia. Still, the reduction in paw withdrawal scores with 6-hydroxyflavone and 7-hydroxyflavone due to cold allodynia was attenuated by bicuculline pretreatment. They did not modify the response observed with flavone or 5-hydroxy flavone (Table 6).

Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives significantly increased the mean change in reaction time in thermal hyperalgesia compared with vehicle treatment. Bicuculline treatment per se did not significantly alter the reaction time compared to the vehicle. However, the mean change in reaction time observed for these monohydroxy flavones in the presence of bicuculline was reduced considerably compared to the individual treatment values. Bicuculline pretreatment had not altered the effect of flavone (Table 6).

| Treatment (mg/kg) | Mechanical allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Cold allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Thermal hyperalgesia | ||

| Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Mean change in reaction time in sec | |

| Vehicle control | 17.17 ± 0.83 | 15.50 ± 1.26 | 14.83 ± 1.01 | 12.67 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.59 |

| Bicuculline (1) | 18.33 ± 1.12 | 18.17 ± 1.08 | 15.67 ± 0.71 | 14.33 ± 1.11 | 1.58 ± 0.38 |

| Flavone (200) | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 7.45 ± 0.63# |

| 5-OHF (200) | 17.50 ± 0.88 | 11.50 ± 1.50* | 16.17 ± 1.13 | 10.67 ±1.30* | 7.86 ± 0.61# |

| 6-OHF (200) | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 1.70* | 15.67 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43* | 8.99 ± 0.74# |

| 7-OHF (200) | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* | 16.83 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ±0.89* | 4.01 ± 0.53# |

| Bicucullin£ + Flavone | 18.00 ± 0.89 | 19.50 ± 0.34 | 11.67 ± 0.80 | 7.00 ± 0.63* | 7.15 ± 0.59 |

| Bicucullin£ + 5-OHF | 18.17 ± 1.28 | 19.17 ± 0.40 | 14.00 ± 1.09 | 9.00 ± 0.36* | 1.16 ± 0.52† |

| Bicucullin£ + 6-OHF | 19.17 ± 0.83 | 18.00 ± 2.00 | 15.83 ± 1.04 | 15.50 ± 1.05 | 0.44 ± 0.78† |

| Bicucullin£ + 7-OHF | 17.17 ± 1.90 | 17.33 ± 1.38 | 14.67 ± 0.95 | 12.83 ± 1.51 | 0.98 ± 0.90† |

| Note: Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations *P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (ANOVA, Paired ‘t’ test) #P<0.001 compared with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) †P<0.05 compared with respective flavone treatment alone @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h prior to the test. £Bicuculline 1 mg/kg, was administered i.p. 15 min prior to flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF (200 mg/kg, s.c) treatment |

|||||

Tab. 6. Effect of GABAergic mechanism and flavone derivatives in paclitaxel-induced mechanical, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice.

Effect of serotonergic mechanism and flavone derivatives

Vehicle or ondansetron treatment had not produced any change in withdrawal score in mice treated with paclitaxel. A statistically significant reduction in the mean paw withdrawal response score was evident in animals after treatment with flavone and different monohydroxy flavones compared to vehicle treatment in both methods of allodynia, as shown in Table 7.

The reduction of paw withdrawal score recorded for flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives was attenuated entirely by pre-treatment with ondansetron in both mechanical and cold allodynia (Table 7).

The mean change in reaction time following ondansetron treatment in mice with paclitaxel-induced thermal hyperalgesia was not significantly different from that with vehicle treatment. Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives significantly increased the reaction time in these animals. However, ondansetron pretreatment attenuated the above response of flavone and all the monohydroxy derivatives (Table 7).

| Treatment (mg/kg) | Mechanical allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Cold allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Thermal hyperalgesia | ||

| Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Mean change in reaction time in sec | |

| Vehicle | 17.17 ± 0.83 | 15.50 ± 1.26 | 14.83 ± 1.01 | 12.67 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.59 |

| Ondansetron (0.1) | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 14.33 ± 1.11 | 13.17 ± 0.83 | 0.80 ± 0.57 |

| Flavone (200) | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 7.45 ± 0.63# |

| 5-OHF (200) | 17.50 ± 0.89 | 11.50 ± 1.50* | 16.17 ± 1.13 | 10.67 ± 1.30* | 7.86 ± 0.61# |

| 6-OHF (200) | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 1.70* | 15.67 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43* | 8.99 ± 0.74# |

| 7-OHF (200) | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* | 16.83 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ±0.89* | 4.01 ± 0.53# |

| Ondansetron£ + Flavone | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 19.83 ± 0.16 | 10.50 ± 0.56 | 11.17 ± 0.79 | 1.46 ± 0.31† |

| Ondansetron£ + 5-OHF | 19.17 ± 1.60 | 18.00 ± 1.10 | 16.17 ± 0.60 | 13.67 ± 1.26 | 1.35 ± 0.92† |

| Ondansetron£ + 6-OHF | 18.00 ± 1.12 | 18.67 ± 0.56 | 15.17 ± 1.27 | 12.83 ± 1.33 | -0.51 ± 0.51† |

| Ondansetron£ + 7-OHF | 19.50 ± 0.34 | 19.00 ± 0.51 | 13.33 ± 0.71 | 12.67 ± 1.17 | 1.08 ± 0.21† |

| Note: Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (ANOVA, Paired ‘t’ test) #P<0.001 compared to with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) †P<0.05 compared with respective flavone treatment alone @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h prior to the test. £Yohimbine 0.1 mg/kg, was administered i.p. 15 min prior to flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF (200 mg/kg, s.c) treatment. |

|||||

Tab. 7. Effect of serotonergic mechanism and flavone derivatives in paclitaxel-induced mechanical, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice.

Effect of adrenergic system and effect of flavone derivatives

Vehicle or yohimbine treatment had not resulted in any significant change in paclitaxel-pretreated mice. Still, treatment with Flavone and different monohydroxy flavones produced a substantial decrease in response score due to allodynia compared to vehicle treatment, as shown in Table 8.

In yohimbine-pretreated animals, flavone, 5-OHF and 7-OHF were unable to reduce the response score. However, the response of 6-OHF remained unaltered by yohimbine pretreatment in mechanical allodynia (Table 8).

The response due to cold allodynia in Flavone, 6-OHF and 7-OHF was not affected by yohimbine pretreatment, but 5-OHF-treated mice annulled this reduction, as shown in Table 8.

The adrenergic antagonist yohimbine did not significantly alter the mean change in reaction time due to paclitaxel-induced thermal hyperalgesia compared to vehicle treatment in mice. Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives, @ 200 mg/kg, significantly increased the reaction time. The response to monohydroxy flavones was attenuated in yohimbine pretreated animals. However, the prolonged reaction time noted in Flavone-treated mice had not been altered by yohimbine pretreatment (Table 8).

| Treatment (mg/kg) | Mechanical allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Cold allodynia Paw withdrawal response score |

Thermal hyperalgesia | ||

| Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Pre-drug administration | Post-drug administration | Mean change in reaction time in sec | |

| Vehicle | 17.17 ± 0.83 | 15.50 ± 1.26 | 14.83 ± 1.01 | 12.67 ± 1.22 | 0.58 ± 0.59 |

| Yohimbine (1) | 14.00 ± 2.01 | 11.67 ± 2.53 | 14.67 ± 0.84 | 13.67 ± 1.02 | 0.17 ± 0.75 |

| Flavone (200) | 18.00 ± 1.03 | 10.33 ± 2.64* | 16.50 ± 0.56 | 9.50 ± 1.17* | 7.45 ± 0.63# |

| 5-OHF (200) | 17.50 ± 0.89 | 11.50 ± 1.50* | 16.17 ± 1.13 | 10.67±1.30* | 7.86 ± 0.61# |

| 6-OHF (200) | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 13.83 ± 1.70* | 15.67 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 1.43 | 8.99 ± 0.74# |

| 7-OHF (200) | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 9.83 ± 1.42* | 16.83 ± 0.47 | 11.50 ±0.89* | 4.01 ± 0.53# |

| Yohimbine£ + Flavone | 18.50 ± 0.50 | 19.83 ± 0.16 | 12.17 ± 0.60 | 7.83 ± 0.47* | 6.55 ± 0.74 |

| Yohimbine£ + 5-OHF | 19.67 ± 0.33 | 19.83 ± 0.17 | 19.67 ± 0.33 | 19.83 ± 0.17 | 2.73 ± 0.57† |

| Yohimbine£ + 6-OHF | 19.00 ± 0.44 | 14.50 ± 1.43* | 16.83 ± 0.60 | 10.33 ±1.11* | 1.90 ± 0.47† |

| Yohimbine£ + 7-OHF | 19.83 ± 0.16 | 18.17 ± 0.60 | 14.50 ± 1.18 | 5.17 ± 0.79* | 0.47 ± 0.11† |

| Note: Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M of six observations P<0.05 compared to the value before drug treatment (ANOVA, Paired ‘t’ test) #P<0.001 compared to with vehicle treatment (ANOVA, Dunnett’s ‘t’ test) †P<0.05 compared with respective flavone treatment alone @All treatment groups received paclitaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h prior to the test. £Yohimbine 1 mg/kg, was administered i.p. 15 min prior to flavone, 5-OHF, 6-OHF or 7-OHF (200 mg/kg, s.c) treatment. |

|||||

Tab. 8. Effect of adrenergic system and effect of flavone derivatives in paclitaxelinduced mechanical, cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice.

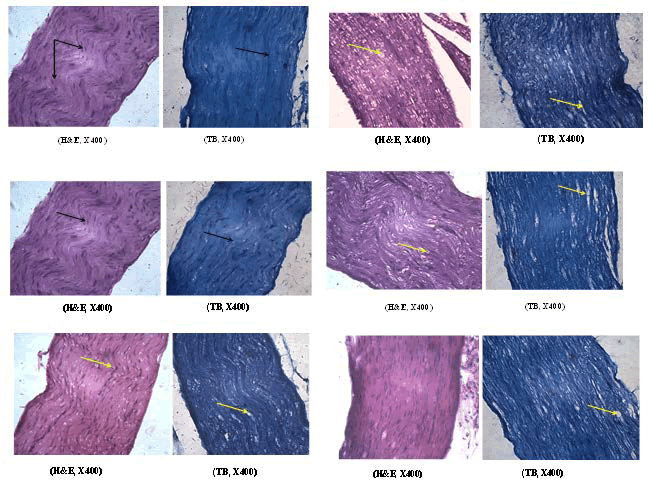

Neuronal changes

The nerve sections obtained from vehicle-treated control animals revealed typical features of axon, myelin sheath and Schwann cells as evident in HandE and toluidine blue (TB) stained sections. However, paclitaxel treatment resulted in a moderate degree of axonal degeneration of the sciatic nerve in mice. The architecture of nerve fibre was distorted. Flavone treatment completely reversed the changes caused by paclitaxel in the sciatic nerve. The nerve sections obtained from mice pretreated with 5-hydroxy Flavone indicated a mild to moderate degree of axonal degeneration. Examination of sciatic nerve sections from mice treated with 6-hydroxy Flavone revealed a minimal to mild degree of axonal degeneration. A very minimal level of axonal degeneration were noticed in 7-hydroxy Flavone pretreated mice when compared to paclitaxel treatment (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Photomicrograph of sciatic nerve section A) Control: Normal schwann cell (black arrow), axon and myelin sheath B) Paclitaxel: Axonal degeneration (Yellow arrow) C) Paclitaxel+Flavone: Normal schwann cell (black arrow), axon and myelin sheath D) Paclitaxel+5-OH flavone: Axonal degeneration (Yellow arrow) E) Paclitaxel+6-OH flavone: Axonal degeneration (Yellow arrow) F) Paclitaxel+7-OH flavone: Minimal axonal degeneration (Yellow arrow).

Discussion

Typical manifestations of neuropathy, namely, mechanical/cold allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia were prominent in mice after 24 hrs of paclitaxel treatement and are consistent with the observations [12]. Morphine administration completely suppressed the expression of the above responses with a significant decrease in the response scores of mechanical and cold allodynia and also offered 87.89% protection against thermal hyperalgesia.

A significant reduction in withdrawal response score for mechanical/ cold allodynia was also evident after flavone and different monohydroxy flavones treatment. Similarly, significant protection against thermal hyperalgesia was observed after administration of the flavone and monohydroxy flavones.

In general, a significant decrease in paw withdrawal response scores for mechanical allodynia was observed only at 200 mg/kg of Flavone and other monohydroxy derivatives, except 5-hydroxy Flavone. However, cold allodynia was significantly attenuated by all flavone derivatives, even at a 100 mg/kg dose. Similarly, a dosedependent increase in maximum protective effect was recorded for all the flavones in thermal hyperalgesia. 6-hydroxy flavone provided a maximum of 44.57% protection.

The efficacy of flavone treatment on chemotherapy-induced neuropathic manifestations was graded: It most potently attenuated cold allodynia, showed intermediate efficacy against thermal hyperalgesia and had the most modest effect on mechanical allodynia.

In the study on antinociceptive activity in flavone and its derivatives, a structure-activity relationship was observed by Thirugnansambantham et al. [10]. The flavone compound exhibited a significant antinociceptive effect. An augmented antinociceptive effect was noted when there is a hydroxyl group at the 5th or 6th position of the flavone nucleus. However, the 7th position possessing a hydroxyl group had reduced antinociceptive activity. This structure-activity relationship holds good even in the present study for its efficacy against CIPN.

The currently employed antidepressants and anticonvulsant drugs to treat CIPN have inherent adverse effects and make the situation complex. Havsteen et al. have proposed that flavonoids exhibit a vast therapeutic window in humans, one that probably surpasses that of any other contemporary drug class [19]. The findings of the present study reveal the availability of a safe group of compounds to manage CIPN compared to other classes of drugs. The acute toxicity studies conducted by Thirugnanasambantham et al. on these compounds indicated that the investigated monohydroxy flavones were safe, without causing mortality in either mice or rats, even at a dose of 2 g/kg, s.c. [10]. The above report reveals the safe nature of monohydroxy flavones employed in the present study.

The present findings also confirm reports from a few earlier studies on the effects of certain flavone derivatives on neuropathy of diverse origin. Peripheral neuropathy in diabetic animals was effectively controlled by quercetin [20,21], naringin [22], nobiletin [23] and rutin [24].

Mechanical allodynia developing after partial sciatic nerve injury was reduced by myricitrin [25]; epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverted thermal hyperalgesia resulting from chronic constriction nerve injury [26] and fisetin attenuated thermal hyperalgesia in mice [27]. Apart from the above, only a few pieces of evidence are available for the effectiveness of flavonoids against neuropathy induced by chemotherapeutic drugs (CIPN). Rutin and quercetin were found to be effective against CIPN induced by oxaliplatin in mice [28].

6-methoxyflavone was found to be effective against CIPN induced by cisplatin [29]. Paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy was attenuated by certain trimethoxy flavones [30]. 3-OH flavone and its dimethoxy derivatives were noted to be effective agents in attenuating the CIPN caused by paclitaxel administration in mice [31].

Different chemotherapy drugs cause neuropathy through distinct mechanisms, each preferentially damaging specific parts of the peripheral nerves-some target the axons (the nerve fibers). In contrast, others damage the myelin sheath (the protective insulation) [32]. Axonopathy is suggested as the primary cause of CIPN in patients with CIPN [33] and in rodent models of CIPN [34,35]. Peripheral nerve fibres vary in morphology, function, degree of myelination and biochemical features. Hence, their susceptibility/sensitivity to the neurotoxic effects of a chemotherapeutic agent differs and the longest nerve fibres have the greatest vulnerability [36], which may be attributed to the increased metabolic demands of larger fibres [37]. Sural nerve biopsy in patients who received paclitaxel showed extreme nerve fibre loss, axonal atrophy with regeneration loss and secondary demyelination [38]. Unmyelinated fibres and terminal nerve arbors were the most important sites of neurotoxicity caused by chemotherapeutic drugs. Intraepidermal Nerve Fibre (IENF) loss or degeneration of terminal arbors was suggested as the most common lesion among different toxic neuropathies [13,39]. Researchers have investigated the antineoplastic drug paclitaxel to assess neuronal degeneration in animal models. Dose-dependent degeneration of intraepidermal nerve fibres, peripheral nerves, dorsal root ganglia and central axons has been documented by many studies [3,13,14,40]. A few drugs, like tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants and SNRI, are currently employed to manage the symptoms of CIPN in patients. However, evidence is not available to indicate whether these drugs can reverse the neurological damage/ degeneration resulting from chemotherapeutic treatment. In the present study, Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives reversed the behavioral manifestations of paclitaxel-induced CIPN. Since the present study investigated all possible mechanisms underlying the protective effect of flavones on paclitaxel-induced CIPN, it was considered worthwhile to extend the research and examine whether flavone treatment altered the histological changes induced by paclitaxel. Concurrent administration of different flavone derivatives provided significant protection against paclitaxelinduced degenerative changes in the sciatic nerve.

In animals treated with flavone, the sciatic nerve sections revealed an almost standard architecture of axons, myelin sheaths and Schwann cells. Only a very minimal degree of axonal degeneration was observed in mice treated with 5-OHF, 6-OHF and 7-OHF. These observations indicate that the structural changes induced by paclitaxel are also partially prevented/reversed by flavone treatment. Paclitaxel is reported to cause various changes in DRG and loss of IENF in the periphery. However, these changes were not examined in the present study. More detailed investigations employing varying doses of flavones and different paclitaxel treatment schedules are warranted to delineate the neuronal protection offered by flavone derivatives fully. Nevertheless, the preliminary observations of the present study indicate that structural alterations in neurons induced by a chemotherapeutic drug are preventable/reversible by the administration of flavone compounds.

Conclusion

Among several groups of chemical compounds, flavonoids have been suggested to target some of the triggering factors in CIPN.

This study explored the potential of Flavone and its monohydroxy derivatives to reduce the symptoms of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN) caused by paclitaxel in preclinical animal models. For this reason, a new group of chemical compounds had been explored and identified as potential drug candidates for treating CIPN. This study also revealed the involvement of neuronal mechanisms, including opioid, alpha-2 adrenergic, serotonergic (5- HT3), GABA and K+ATP ion channels, in the protective effects of different flavone compounds. An analysis of the structureactivity relationships of the tested flavones indicates that 5-OHF and 6-OHF exhibit the most excellent efficacy against CIPN in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs. These evidences also reveal the possible use of flavone compounds in various types of neuropathic pain, which has to be confirmed by future research.

Ethics

IAEC of Meenakshi Medical College Hospital and Research Institute approved the study (Registration No: 765/03/Ca/ CPCSEA; Decision No: KN/COL/3408/2014 and 002/2015, dated 22nd July 2014 and 24th June 2015).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to Meenakshi Medical College Hospital and Research Institute for the infrastructure and research facilities in conducting the research.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Financial Disclosure

None of the financial agency or grants are available for this research.

Data Available Statement

The corresponding author may provide study data upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: PK, VSU; Methodology: PK, VSU, JN; Software: PK, VSU; Validation: PK,VS, JS; Formal analysis: PK, VS, JS; Investigation: PK, VS, JN; Resources: PK, VS. Data curation: PK,VS, JS, JN; Writing-original draft: PK, NP, VSU; Writing-review and editing: PK, NP; Visualisation: PK, NP; Supervision: VSU; Project administration: VSU; Funding acquisition: Nil.

References

- Ferrier J, Pereira V, Busserolles J, Authier N, Balayssac D. Emerging trends in understanding chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013; 17:364.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rowinsky EK, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR, Donehower RC. Neurotoxicity of Taxol. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1993: 107-115.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flatters SJ, Dougherty PM, Colvin LA. Clinical and preclinical perspectives on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2017; 119:737-749.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scripture CD, Figg WD, Sparreboom A. Peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel: recent insights and future perspectives. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006; 4:165-172.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burda S, Oleszek W. Antioxidant and antiradical activities of flavonoids. J Agric Food Chem. 2001; 49:2774-2779.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vidyalakshmi K, Kamalakannan P, Viswanathan S, Ramaswamy S. Antinociceptive effect of certain dihydroxy flavones in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010; 96:1-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vidyalakshmi K, Kamalakannan P, Viswanathan S, Ramaswamy S. Anti-inflammatory effect of certain dihydroxy flavones and the mechanisms involved. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2012; 11:253-261.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandurangan K, Krishnappan V, Subramanian V, Subramanyan R. Antinociceptive effect of certain dimethoxy flavones in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014; 727:148-157.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandurangan K, Krishnappan V, Subramanian V, Subramanyan R. Anti-inflammatory effect of certain dimethoxy flavones. Inflammopharmacology. 2015; 23:307-317.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thirugnanasambantham P, Viswanathan S, Mythirayee C, Krishnamurty V, Ramachandran S, et al. Analgesic activity of certain flavone derivatives: A structure-activity study. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990; 28:207-214.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arivudainambi R, Viswanathan S, Thirugnanasambantham P, Reddy KM, Dewan MI, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of flavone and its hydroxy derivatives: A structure activity study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 1996; 58:18-21.

- Hidaka T, Shima T, Nagira K, Masahiro L, Takafumi N, et al. Herbal medicine Shakuyakukanzo-to reduces paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in mice. Eur J Pain. 2009; 13:22-27.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bennett GJ, Liu GK, Xiao WH, Jin HW, Siau C. Terminal arbor degeneration: a novel lesion produced by the antineoplastic agent paclitaxel. Eur J Neurosci. 2011; 33:1667-1676.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toma W, Kyte SL, Bagdas D, Alkhlaif Y, Alsharari SD, et al. Effects of paclitaxel on the development of neuropathy and affective behaviors in the mouse. Neuropharmacol. 2017; 117:305-315.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andoh T, Kitamura R, Fushimi H, Komatsu K, Shibahara N, et al. Effects of Goshajinkigan, Hachimijiogan, and Rokumigan on mechanical allodynia induced by paclitaxel in mice. J Tradit Complement Med. 2014; 4:293-297.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flatters SJL, Bennett GJ. Ethosuximide reverses paclitaxel and vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2004; 109:150-161.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ta LE, Philip AL, Anthony JW. Mice with cisplatin and oxaliplatin-induced painful neuropathy develop distinct early responses to thermal stimuli. Mol Pain. 2009; 5:9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bala U, Tan KL, Ling KH, Cheah PS. Harvesting the maximum length of sciatic nerve from adult mice: A step-by-step approach. BMC Res Notes. 2014; 7:714.

- Havsteen BH. The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002; 96:67–202.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anjaneyulu M, Chopra K. Quercetin, a bioflavonoid, attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 27:1001–1005.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Narenjkar J, Roghani M, Alambeygi H, Sedaghati F. The effect of the flavonoid quercetin on pain sensation in diabetic rats. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2011; 2:51.

- Kandhare AD, Raygude KS, Ghosh P, Ghule AE, Bodhankar SL. Neuroprotective effect of naringin by modulation of endogenous biomarkers in streptozotocin induced painful diabetic neuropathy. Fitoterapia. 2012; 83:650-659.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parkar N, Addepalli V. Effect of nobiletin on diabetic neuropathy in experimental rats. Austin J Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 2:1028.

- Al-Enazi MM. Ameliorative potential of rutin on streptozotocin-induced neuropathic pain in rat. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2003; 7:2743-2754.

- Meotti FC, Missau FC, Ferreira J, Pizzolatti MG, Mizuzaki C, et al. Anti-allodynic property of flavonoid myricitrin in models of persistent inflammatory and neuropathic pain in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006; 72:1707-1713.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xifro X, Vidal-Sancho L, Boadas-Vaello P, Turrado C, Alberch J, et al. Novel epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) derivative as a new therapeutic strategy for reducing neuropathic pain after chronic constriction nerve injury in mice. PloS One. 2015; 10:e0123122.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Wang C, Cui WG, Ma Q, Zhou WH. Fisetin exerts antihyperalgesic effect in a mouse model of neuropathic pain: Engagement of spinal serotonergic system. Sci Rep. 2015; 5:9043.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azevedo MI, Pereira AF, Nogueira RB, Rolim FE, Brito GA, et al. The antioxidant effects of the flavonoids rutin and quercetin inhibit oxaliplatin-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Mol Pain. 2013; 9:1744-8069.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahid M, Subhan F, Ahmad N, Sewell RD. The flavonoid 6-methoxyflavone allays cisplatin-induced neuropathic allodynia and hypoalgesia. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017; 95:1725-1733.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nadipelly J, Sayeli V, Kadhirvelu P, Shanmugasundaram J, Cheriyan BV, et al. Effect of certain trimethoxy flavones on paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice. Integr Med Res. 2018; 7:159-167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sayeli V, Nadipelly J, Kadhirvelu P, Cheriyan BV, Shanmugasundaram J, et al. Antinociceptive effect of flavonol and a few structurally related dimethoxy flavonols in mice. Inflammopharmacology. 2019; 27:1155-1167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han Y, Smith MT. Pathobiology of cancer chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Front Pharmacol. 2013; 4:156.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Burton AW, Villareal H, Giralt S, et al. Quantitative sensory findings in patients with bortezomib-induced pain. J Pain. 2007; 8:296-306.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cavaletti G, Gilardini A, Canta A, Rigamonti L, Rodriguez-Menendez V, et al. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: A neurophysiological and pathological study in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2007; 204:317-325.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boyette-Davis J, Dougherty PM. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Exp Neurol. 2011; 229:353-357.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez G, Sereno M, Miralles A, Casado-Sáenz E, Gutiérrez-Rivas E. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: clinical features, diagnosis, prevention and treatment strategies. Clin Translat Oncol. 2010; 12:81-91.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mironov SL. ADP regulates movements of mitochondria in neurons. Biophys J. 2007; 92:2944-2952.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sahenk Z, Barohn R, New P, Mendell JR. Taxol neuropathy: Electrodiagnostic and sural nerve biopsy findings. Arch Neurol. 1994; 51:726-729.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng H, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2012; 238:225-234.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wozniak KM, Nomoto K, Lapidus RG, Wu Y, Carozzi V, et al. Comparison of neuropathy-inducing effects of eribulin mesylate, paclitaxel, and ixabepilone in mice. Can Res. 2011; 71:3952-3962.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]