Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 11

Dysphagia-Optimized Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy versus Standard Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer Patients

Sara M El-badawy1*, Nehal Elmashad1, Rasha Khedr1 and Fatma Zakaria1Sara M El-badawy, Clinical Oncology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt, Email: sara.elbadawy@med.tanta.edu.eg

Received: 01-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-176202; , Pre QC No. OAR-25-176202 (PQ); Editor assigned: 03-Nov-2025, Pre QC No. OAR-25-176202 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Nov-2025, QC No. OAR-25-176202; Revised: 24-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-176202 (R); Published: 28-Nov-2025

Abstract

Purpose: Improving the functional outcomes of head and neck cancer (HNC) patients is pivotal, as healthier patients are increasingly cured with concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT), with a real risk of pharyngeal cripples. Current evidence confirms that a significant relationship exists between pharyngeal constrictor muscle (PCM) radiation and persistent dysphagia. Therefore, our study was to determine if reducing the radiation dose to the PCM via DO-IMRT (dysphagia optimized), which would improve swallowing compared with S-IMRT (standard) and to investigate the longitudinal pattern of swallowing function post radiotherapy via the MDADI (MD Anderson dysphagia inventory). Methods and Materials: This prospective, parallel, single-blinded, randomized controlled study included patients who underwent definitive CCRT for pathologically confirmed HNC (squamous cell carcinoma). Evaluations were conducted up to 6 months following treatment, in addition to the basal assessment. Radiological assessment was requested after radiotherapy, and Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) were applied. Results: Dysphagia as a toxicity measured by CTCAE was significantly lower in the DO-IMRT, which improved at 6 months better than the base line assessment. The MDADI longitudinal scores of DO-IMRT tended to significantly improve, with a mean difference of 27% in swallowing function and a persistent effect at the 6-month assessment. The response assessment revealed no significant P value. Conclusions: We concluded that DO-IMRT is superior in preserving swallowing function over S-IMRT; and has a positive impact on QOL in HNC survivors.

Keywords

Head and Neck Cancer; DO-IMRT; Pharyngeal Constrictor Muscle; Quality Of Life

INTRODUCTION

HNC is a life-altering illness [1], and it is the sixth most prevalent form of cancer globally and on the rise [2].

Regarding ESHNO (Egyptian Society of Head and Neck Oncology) statistics, 4,000 Egyptians get HNC every year, accounting for 17: 20 %, among which almost 1,900 die (47.5 %) [3]. Depending on where the primary tumor is located and how it interacts with different risk factors, HNC can present differently clinically.

Treatment is multidisciplinary. Aspects such as nutrition, oral care, and preservation of swallowing and speech therapy should be considered [4]. Radiotherapy can be a substitute for surgical resection in the early stages [5].

Patients may undergo CCRT for locally advanced disease or through postoperative radiotherapy. The goal of radiotherapy is to preserve organ function, as does the use of chemo-radiotherapy to prevent laryngeal resection [6]. Definitive therapy with CCRT is considered the standard of care for patients. Over the years, IMRT has become a widely used method for HNC because it can precisely target the main tumor and vulnerable lymph nodes while minimizing the dose to the surrounding healthy tissues, thereby reducing morbidity and improving target coverage with better regional control [7, 8]. Several OARs are routinely contoured on each patient planning CT, and optional OARs include constrictor muscles [9].

Dysphagia is one of the most important radiation adverse impacts [10, 11] with incidence rates of significant dysphagia ranging from 12:50 %, and it varies depending on multiple factors, such as tumor location, stage of disease, and treatment modality [12]. Additional outcomes of swallowing dysfunction include extended reliance on feeding tubes, psychological issues, and worsened HR-QOL [13, 14]. Regardless of the cause, post-treatment dysphagia affects QOL. Assessment of HR-QOL is important for evaluating overall treatment effectiveness, informing patients and healthcare providers about the treatment outcomes, and assisting in decision-making. Although trials are already aiming to limit the radiation dose to all at-risk swallowing organs as accepted, sparing them should be a priority since it is a critical factor in later inadequate functional results [15, 16].

Current evidence confirms that a significant relationship exists between radiation to constrictors and the incidence of prolonged swallowing difficulty [17].The query of whether function-preserving IMRT actually improves function and QOL is still open, despite the published literature on optimizing radiotherapy techniques to recover from persistent swallowing disturbance. We aimed to determine the superiority of DO-IMRT over S-IMRT in preserving swallowing function.

Patients and Methods

Our study protocol was a prospective, parallel, single-blinded (patients), randomized controlled study that included 70 patients underwent definitive chemo-radiation and patients who received radiation alone, for pathologically confirmed H&N (SCC), at Department of Clinical Oncology, Tanta University Hospitals, Egypt from December 2021 to December 2023 then last follow up was in first of July 2024.

We chose patients at random (1:1) to be managed either with standard IMRT or dysphagia-optimized IMRT.

The randomization technique is simple randomization in detail; simply newly diagnosed patients presented in our hospital clinic A & met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the S-IMRT group. Similarly, newly diagnosed patients presented in our hospital clinic B & met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the DO-IMRT group.

To choose the right sample size for this study, a power analysis was carried out to guarantee that there would be enough power to identify a significant effect, using G*power version 3.1.9.4 (RRID: SCR_013726).

This sample size ensured that this study had sufficient power to detect large-sized effects, which gave us the desired power of 0.9449534, would support the study design, enhance the validity of the findings, and provide confidence in the potential to draw robust conclusions from the results.

Inclusion Criteria

- Age ≥ 18 years.

- Patient treated with radiotherapy for HNC (squamous cell carcinoma).

- Disease of T1 to T4, N0 to N3, and non-metastatic disease.

- CCRT is the planned treatment.

- Radiation alone was also allowed.

- Adequate cognitive ability to complete assessment questionnaires.

Exclusion Criteria

- Records demonstrating a history of swallowing difficulties unrelated to HNC.

- Prior radiation treatment to the head and neck area.

- Involvement of the retropharyngeal node, posterior pharyngeal wall, or post-cricoid.

- Major surgery excluding biopsy or tonsillectomy.

- History of tracheostomy insertion.

- Any proven cancer occurred within the last 2 years.

Objectives

- In comparison with S-IMRT, to ascertain whether swallowing would be improved by lowering the dose to the constrictors by Do-IMRT.

- The MDADI was used to examine the longitudinal swallowing pattern after radiotherapy.

- Examine the effects of Do-IMRT:

- Dietary norms according to the PSS-HN questionnaire;

- Swallowing adequacy by the water swallow test;

- Toxicity was assessed via the NCI-CTCAE (v5.0).

- The UW-QOL questionnaire (v.04) was used to evaluate patient-reported quality of life.

- Radiological assessment by CT or MRI was requested 6 weeks post radiotherapy, and RECIST was applied.

In addition to the baseline evaluation conducted prior to the initiation of radiation therapy, evaluations were requested at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months following treatment.

Radiotherapy

Patients received up to 60 to 70 Gy in 30 to 35 fractions. Treatment was delivered via the IMRT techniques S-IMRT and DO-IMRT. Patients were randomized into two study groups:

- There were 35 patients, in the S-IMRT arm which is the current gold standard.

- The DO-IMRT arm consisted of 35 patients.

By steering clear of any possible bias the clinician might introduce during delineation, randomization took place after target contouring, guaranteeing uniformity in the volumes of the standard and experimental treatments. With the goal of finishing radiotherapy in 6-7 weeks, any treatment gaps were addressed in accordance with the guidelines of the Royal College of Radiologists.

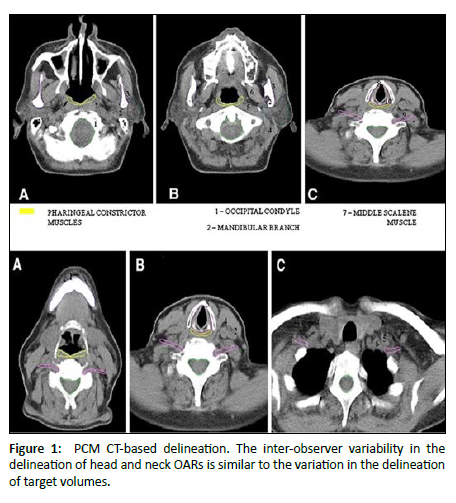

Contouring the PCM was based on the published contouring guidelines defined by Christianen et al. in conjunction with the PATHOS trial atlas [18, 19] and the dose-to-volume limitations for radiotherapy-at-risk organs (CORSAIR): a practical overview of a multicenter multidisciplinary all-in-one approach [20].

DO-IMRT

By designating them as organs at risk, DO-IMRT was used to lower the dose to the PCM, optimizing the treatment strategy to adhere to predetermined dose constraints.

The part of the constrictors outside of the high CTV was intended to be spared by the DO-IMRT technique.

In our study, the dosimetric dose limitation for the constrictors was defined as mean doses to the constrictors exceeding 50 Gy, since they are linked to the risk of dysphagia [21].

A head CT scan window width of 350 HU with a center level of 35 HU was used to contour the PCM.

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

NCI CTCAE v5.0: (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, published in 2017)

It is a descriptive tool utilized for side effect assessment. A severity scale is provided [22].

Performance status (PSS-HN) scale for head and neck cancer:

- Diet norms: To start, we asked the patient what foods he had been consuming. “What foods were hard to eat?” We asked. As we progressed up the scale, we asked the patient if he was consuming the foods that were shown in each category. We used solid food to determine the patients’ score if they were able to eat orally in addition to utilizing a feeding tube.

- Public eating: We used the scale to score the patient by asking him where he ate (at home, at a restaurant, at the homes of friends or family, etc.) and with whom he dined (always by himself, with friends or family, etc.). We questioned the patient if he had selected less messy, softer, or other foods when sharing a meal. Our inpatient score was 999.

- Understandability of speech: This scale was scored on the basis of how well the interviewer understood the patient during the conversation [23] [Figure 1].

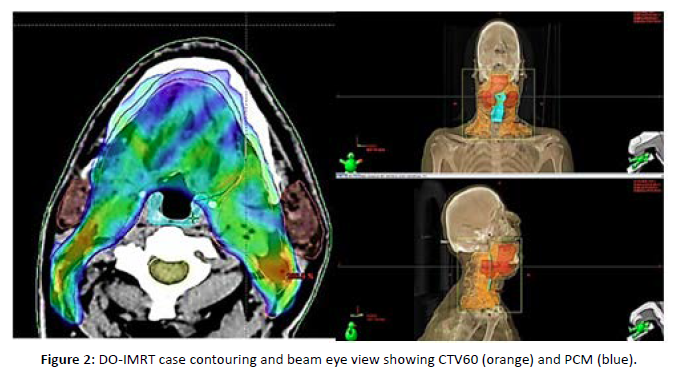

Figure 1: PCM CT-based delineation. The inter-observer variability in the delineation of head and neck OARs is similar to the variation in the delineation of target volumes.

100-Ml Water Swallowing Test

Patients drank 100 mL of water as fast as they could after getting the go signal. The swallowing time was recorded by a stopwatch with a readability of 1 ms from the start to the end of the test. Notably, the end of the WST was known visually by the thyroid cartilage in its position for patients who had already finished the cup of water. Coughing from the start to one minute after the completion of the test was recorded as a sign of choking. Regardless of whether they had completed the cup, patients who choked while swallowing were instructed to stop the test right away. In these situations, the moment choking occurred, the stopwatch was stopped. The amount consumed divided by the time on the stopwatch was used to calculate the swallowing speed. Assessing swallowing speed in the test seemed to be a helpful bedside objective test for the early detection of dysphagia because of its high sensitivity and ease of use [24].

University of Washington QOL Questionnaire

During their previous 7 days, the questionnaire inquired about patient health and general well-being. Ten domains were assessed: shoulder, swallowing, chewing, speech, appearance, activity, recreation, pain, taste, saliva, and overall QOL. The mood and anxiety domains were included in version 4 [25].

M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory

This questionnaire included 4 subgroups (functional, emotional, global, and physical). Each group had a 5-point scale, with lower scores indicating worse function [26].

Response Evaluation

For measuring lesions chosen for response assessment, CT and MRI are the most effective available techniques currently in use.

The objective evaluation of tumors via endoscopy and laparoscopy has not yet been thoroughly and extensively validated. Only certain facilities may have the advanced equipment and high level of expertise needed for their applications in this particular setting.

However, when biopsies are obtained, such methods can be helpful in verifying the full pathological response.

Chemotherapy

Induction chemotherapy followed the department’s standard policy when indicated; by a multidisciplinary team, a maximum of three platinum-based chemotherapy cycles were given before starting radiotherapy. All patients were advised to receive concurrent chemotherapy. Radiotherapy alone was allowed when indicated. The standard regimen was 40 mg/m2 cisplatin administered weekly concomitantly with the radiotherapy schedule. Carboplatin (AUC 6) D1 every 21 days may be used if patients have comorbidities or develop cisplatin-related toxicity.

Statistical Data Analysis

Version 29 (released in 2023) of the IBM SPSS software (RRID: SCR_002865) was used to analyze the data, and numbers and percentages were used to describe the qualitative data.

The range, mean, standard deviation (SD), and interquartile range (IQR) were used to characterize the quantitative data, whereas the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to confirm the distributions’ normality. The results’ significance was assessed at the five percent level (P value).

Privacy Provision

Every patient had a file with a private code number that included their questionnaire and private information, and the privacy of all patient data was ensured.

Informed consent

All the participants provided their consent (to participate and publish) after being fully informed of the risks and benefits. The participants and the ethical committee were promptly informed of any unforeseen risks that arose during the study.

CASE

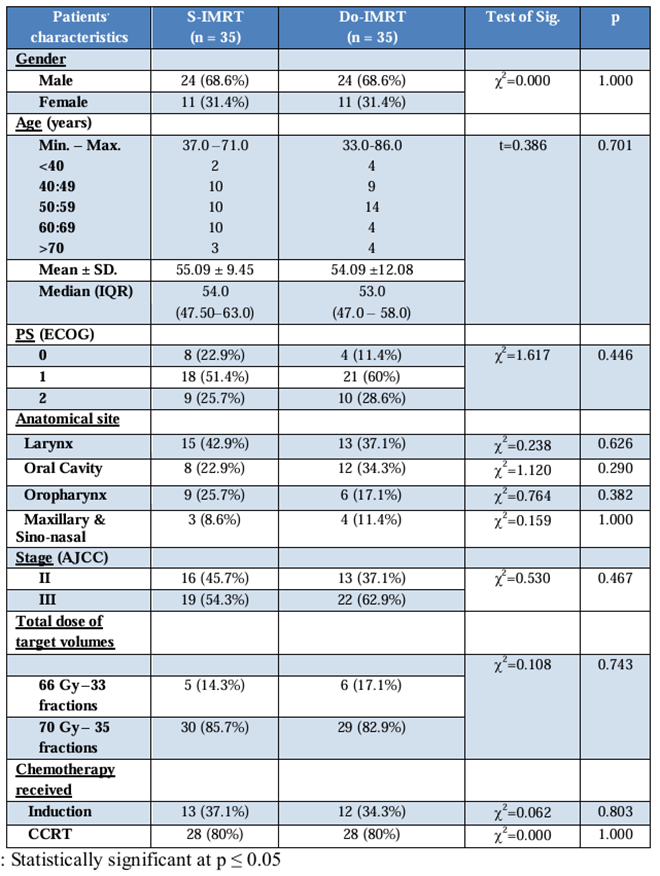

A 49-year-old male patient with head and neck SCC T2N2cM0 received definitive CCRT, with a total dose of 70 Gy by DO-IMRT. The mean PCM dose was 47 Gy. The composite MDADI score was 92 at 6 months (high functioning with better QOL), whereas it was 76 at baseline and 60 after radiotherapy. In our case, the PCM was contoured in blue and spared outside the CTV as much as possible with a mean dose of 47 Gy. The beam eye view shows CTV 70 of the gross tumor and bilateral neck involvement in red and CTV 60 of the bilateral neck irradiation of high-risk areas in orange, with the PCM in blue spared outside [Figure 2].

Figure 2: DO-IMRT case contouring and beam eye view showing CTV60 (orange) and PCM (blue).

Results

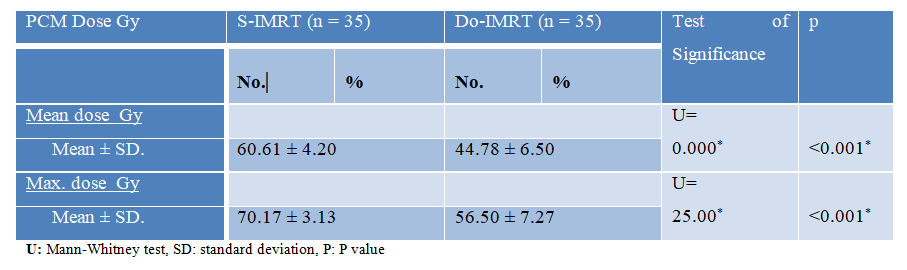

There is no significant difference between observed patient characteristics in both groups; the need to reduce confounding variables that could compromise the reliability of the outcomes was reflected in our study methodology, which balanced the characteristics of patients across treatment groups regarding age, performance status, stage, total dose of target volumes, the most important chemotherapy received, and baseline assessment of toxicity and QOL. Approximately 68.6% of our patients were male, the median age was 53 years in the Do-IMRT group and 54 years in the S-IMRT group, and most of our patients had performance one [Table 1].

Table 1: Comparison between the Two Studied Groups According To Patients’ Characteristics.

In the Do-IMRT group, 62% of patients and in the S-IMRT group, 54% of patients had stage III disease.

Approximately 85% of our patients received a total dose of target volumes radiation of 70 GY, approximately 80% of whom received concurrent chemo-radiotherapy, whereas 34.3% of our patients in the Do-IMRT group and 37.1% of our patients who received S-IMRT received induction chemotherapy. The only significant difference was in the PCM dose, with a mean dose of 44.7 GY for DO-IMRT and 60.6 GY for S-IMRT [Table 2].

Table 2: PCM dose comparisons between the two groups under study.

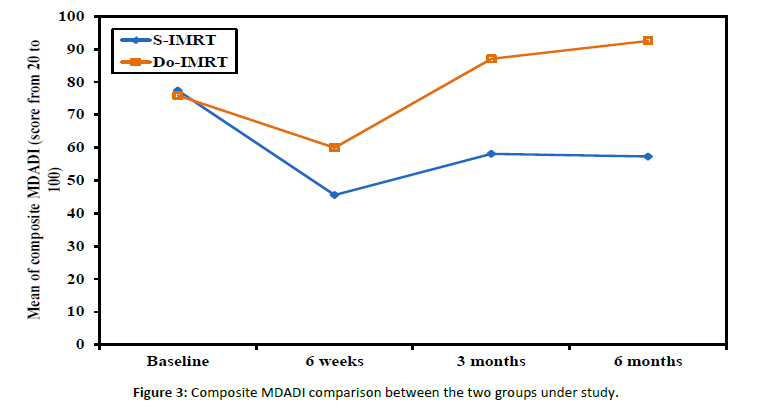

The MDADI questionnaire scores showed significant difference with high-functioning DO-IMRT scores [Figure 3].

Figure 3: Composite MDADI comparison between the two groups under study.

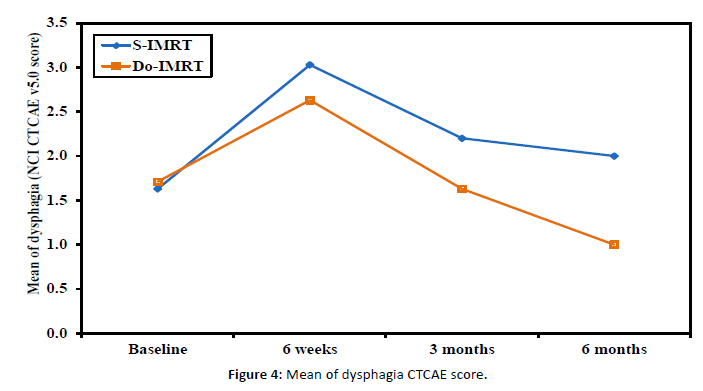

Examining how DO-IMRT scores vary over time from baseline scores revealed a significant pattern, with a persistent significant longitudinal effect at the 6-month assessment [Figure 4].

Figure 4: Mean of dysphagia CTCAE score.

The two main categories of dysphagia assessment tools are as follows:

- Subjective: CTCAE v.5.0 and PSS-H&N.

- Objective: 100-ml WST.

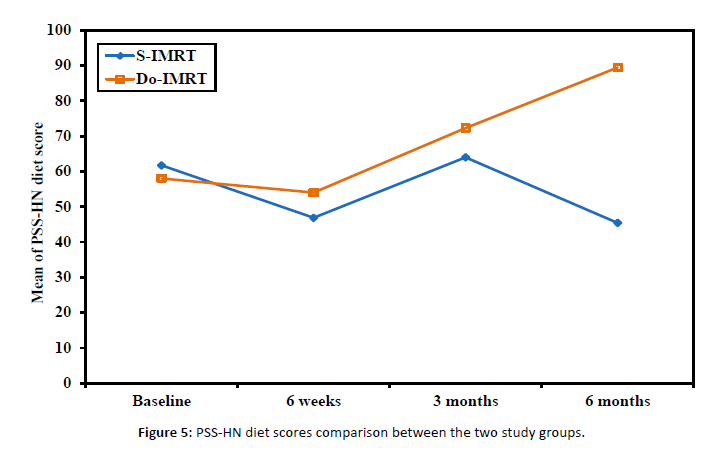

Dysphagia assessment by CTCAE v.5.0 was less by DO-IMRT with significant difference a long post-radiotherapy assessments over 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months [Figure 5].

Figure 5: PSS-HN diet scores comparison between the two study groups.

Additionally, dysphagia improvement with DO-IMRT at the 6-month assessment was better than that with the baseline assessment.

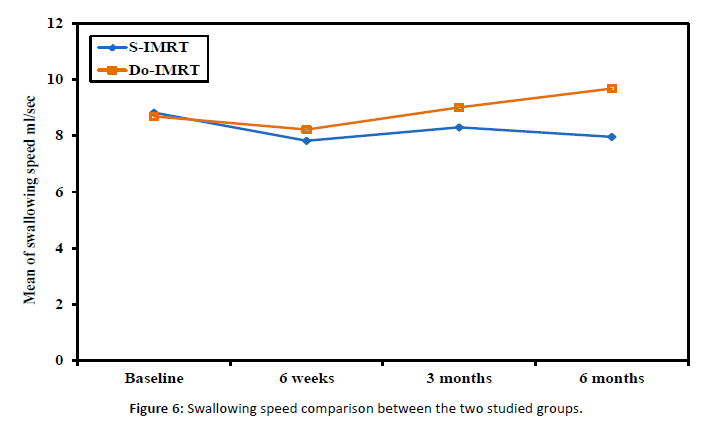

The scoring of PSS-HN consists of 3 main categories: diet norms, public eating, and speech understandability [Figure 6].

Figure 6: Swallowing speed comparison between the two studied groups.

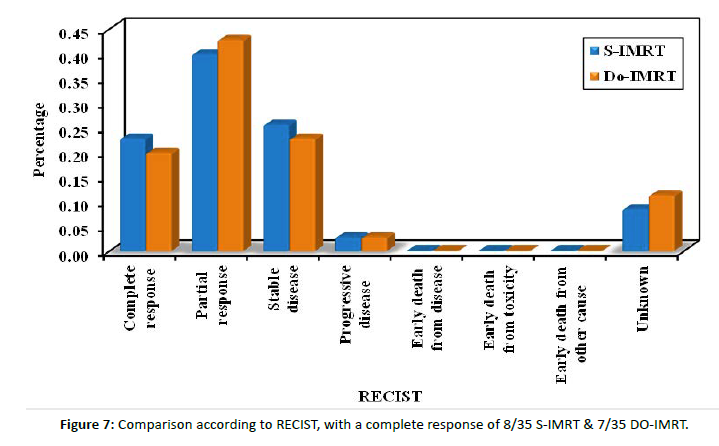

Figure 7: Comparison according to RECIST, with a complete response of 8/35 S-IMRT & 7/35 DO-IMRT.

The normalcy of diet curve showed significant improvement with DO-IMRT.

Post-radiotherapy assessments in the DO-IMRT arm revealed an average score of 50, which indicates soft chewable foods, which improved over time with a score of 89 at the 6-month assessment, indicating a full diet with the intake of extra fluids.

Additionally, according to the water swallowing test, the swallowing speed significantly improved with DO-IMRT, and the average speed was near normal at the 6-month assessment of DO-IMRT but deteriorated with S-IMRT.

Dysphagia-related QOL assessment:

- MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI).

- Washington University QOL Scale (UW-QOL).

The Washington University QOL scale consists of twelve domains with different scoring systems, as lower scores indicate better QOL, with the domain of assessment of swallowing difficulty being significantly lower with DO-IMRT.

Additionally, all questionnaire domain scores were generally lower with DO-IMRT, resulting in better QOL. Similar to the global assessment of QOL by the UW-QOL questionnaire, lower scores indicate better QOL.

Post-radiotherapy assessments revealed worsening of the patient’s general condition.

However, at the 3- and 6-month assessments, there was more significant improvement in the Do-IMRT group.

An assessment of the response of all our patients revealed a response in 22 patients in both groups and stable disease in 9 patients in the S-IMRT group and 8 patients in the DO-IMRT group.

Only one patient in each group had progressive disease. The response assessment revealed no significant P value between the treatment groups.

Discussion

The rising prevalence of HNC in Egypt highlights the necessity for more comprehensive research covering all its aspects, particularly QOL. Assisted feeding and dysphagia are the results of radiation toxicity to the swallowing structures. Numerous reports indicate severe dysphagia associated with the CCRT approach, i.e., feeding tube dependency within the first year has a major QOL effect [27]. Additionally, much detailed research about the toxicity of swallowing muscles obviated that dysphagia after treatment for HNC is strongly related to the dose to the pharyngeal constrictors [28]. Our study sheds light on the connection between sparing the pharyngeal constrictors from high CTV through DO-IMRT and the influence of treatment-related dysphagia on QOL. The oral cavity, cricopharyngeus, cervical esophagus, supraglottic/glottic larynx, and pharyngeal constrictor muscles are all integral to swallowing. To avoid under-dosing target CTVs and influencing response, most swallowing structures should not be used for treatment plan optimization [19].

The overlap of PCM hindered the establishment of suitable dose-volume constraints, potentially leading to significant variability. Consequently, we considered the 3 parts as one muscle with a mean dose < 50 GY, as we only spared the PCM part involved in certain high CTVs according to the primary site.

In a study that also sought to evaluate the impact of the margin (CTV-PTV margin) applied to the clinical target volume to create the planning target volume on the quality of DO-IMRT plans that comply with the protocol, the majority of plans failed to meet the ideal plan inferior PCM constraint of less than 20 GY [29].

The PCM was delineated by the main investigator and reviewed by the radiation oncologist, and then the physicist reviewed the DVH to maintain proper target coverage. Three-phase planning assisted with reducing subjectivity in the optimization of plans and established a more objective benchmark for comparison.

Christianen et al. initially identified to a diverse cohort of patients whose mean doses to the SPC and supraglottic larynx were the most predictive of grade 2 dysphagia 6 months after treatment completion [30].

The same study also demonstrated that radiation dose to the supraglottic larynx lessened over time, leaving the PCM as the sole significant variable [30].

The constrictor mean dose was also a strong predictor of subsequent functional impairment, according to the systematic review by Duprez et al [30].

Van der Molen L. et al. evaluated the dose parameters of swallowing and masticatory structures and demonstrated a correlation between them and dysphagia in HNC patients. Additionally, they found that the constrictor mean dose was a powerful predictor [31].

Eisbruch et al. found that thickening of the supraglottic larynx and pharyngeal constrictors was the most likely cause of swallowing difficulty in patients receiving radiation therapy [15].

According to a study by Levendag et al., the mean total dose to the superior and middle constrictor muscles was significantly correlated with the probability of swallowing difficulties [32].

However, in the DARS trial, it was not clear which pharyngeal constrictor muscle segments were most crucial for maintaining swallowing function [33].

The Dutch research team justified the 6-month period following treatment by arguing that it was a good indicator of swallowing decline at later periods before reaching a plateau [30].

Toxicity assessment related to pharyngeal dysphagia can be divided into two main categories:

- Subjective: CTCAE v.5.0 and PSS-H&N.

Baseline assessment of dysphagia by CTCAE v.5.0 indicated no significant difference (P value 0.529), with an average score of 1, i.e., symptomatic and able to eat a regular diet, and 2, i.e., symptomatic and altered swallowing, ensuring that any swallowing changes were attributable to the treatment.

Post-radiotherapy assessments revealed statistically significant differences (P value <0.001) between DO-IMRT and S-IMRT, and the average score for DO-IMRT, post-radiotherapy ranged from 2 to 3, i.e., severely altered swallowing, which was improving over time with a score of 1 at the 6-month assessment.

The score of PSS-HN, the average score in DO-IMRT post radiotherapy, ranged from 40, i.e., soft foods requiring no chewing, to 50, i.e., soft foods, which improved over time with a score of 89, i.e., a full diet with intake of extra fluids at the 6-month assessment.

Compared with those who received S-IMRT, more participants who received DO-IMRT reported diet norms and eating, publically, with scores of greater than seventy-five or ninety at 3, 12, and 24 months.

Pharyngeal muscle function had no effect on speech understandability in the DARS trial. [33]

Contrary to that, we found that post-radiotherapy assessments were statistically significant (P value <0.001) between DO-IMRT and S-IMRT, with the mean score improving to 67.86, i.e., no restrictions in place, but were restricted to the public in DO-IMRT at 6 months.

Additionally, we found that the average score for DO-IMRT, post-radiotherapy ranged from 50, i.e., face-to-face contact necessary, to 75, i.e., understandable most of the time, occasional repetition necessary (P value <0.001), which improved over time with a score of 83.5, i.e., ranging from understandable most of the time, necessitating repetition, to being fully understandable at the 6-month assessment (P value <0.001).

- Objective: the WST

Post-radiotherapy assessments showed a statistically significant difference (P value <0.001) between Do-IMRT and S-IMRT. The average swallowing speed was near normal (>10 ml/sec) in the 6-month assessment in the DO-IMRT arm but deteriorated to 7.96 ml/sec in the S-IMRT arm.

This, in succession, negatively impacted patients’ QOL, but data concerning HR-QOL and toxicity are limited.

The findings of Johannes A. Langendijk et al. and Ramaekers BL et al. indicated that while xerostomia was the most commonly reported condition, dysphagia had the greatest impact on HR-QOL [34].

In their study comparing the effects of toxicity on QOL, Langendijk et al. came to the conclusion that radiotherapy techniques had to concentrate not only on lowering doses to the salivation glands but also, in addition, on swallowing-involved structures [34]. There are several other measuring tools of dysphagia-related QOL, including the MDADI and Washington University QOL questionnaires. We relied on the MDADI composite score as the main toxicity measure since it is the most popular and reliable patient-reported questionnaire for evaluating swallowing after HNC treatment [33]. Before starting radiotherapy, baseline assessment showed no statistical difference (P value 0.072) with a mean score of 75.92 (SD ± 3.27) in the DO-IMRT group. A significant pattern (P value <0.001) regarding group differences was revealed by examining the longitudinal pattern of DO-IMRT and MDADI scores as they changed over time from baseline scores, with a mean difference of 27% improvement in swallowing function from the 6-week to the 3-month assessments (87 and 60) with a persistent significant longitudinal effect and a mean difference of 5.5% improvement at the 6-month assessment. Hutcheson et al. discovered that clinically significant between-group differences in swallowing ability, oral diet intake ability, and diet normalcy, as measured by the PSS-HN, are statistically linked to a difference of ten points in the MDADI score [35]. The DARS trial showed a between-group difference of 7 points (mean score DO-IMRT 77.7 [SD 16.1] versus S-IMRT 70.6 [17.3]) in the MDADI composite score [35]. However, Carlsson et al. suggested that smaller differences in MDADI were clinically significant [36]. In general, UW-QOL scores were lower (i.e., better QOL) in DO-IMRT than in S-IMRT, especially for pain (P value <0.001) and swallowing (P value 0.007); also, DO-IMRT improved QOL scores in the 6-month assessment to a level near or better than the baseline assessment. In line with the DARS trial, comparing S-IMRT and DO-IMRT, DO-IMRT significantly improved the UW-QOL questionnaire swallowing domain score at three and twelve months as well as across all domains. The DO IMRT group included more patients who reported the highest possible score [33]. Radiological assessment of response by CT and/or MRI was done at 6-8 weeks post-radiotherapy for all patients. The RECIST criteria were applied with response of 22 patients in both arms, complete response with P value (0.771), partial response with P value (0.808), and stable disease in 9 patients in the S-IMRT group and 8 patients in the DO-IMRT group (P value 0.780). Progression was considered in 4 patients receiving S-IMRT and 5 patients receiving DO-IMRT. Planning target volumes and loco-regional control rates were not compromised in a later review that looked at swallow-sparing radiation protocols, to lessen the severity of dysphagia [35]. Feng and colleagues demonstrated that utilizing DO-IMRT to lower the radiation dose to PCM could result in favorable swallowing outcomes without a rise in tumor recurrence locally in the area of spared constrictors [4]. So, why do we not focus on establishing dysphagia-optimized IMRT strategies, especially in the era of the strict healthcare budgets that are in place right now?

We must acknowledge potential limitations of our study, as it was a single-center study, and the follow-up time was not long enough. Large-scale prospective clinical studies are recommended.

Conclusion

- Compared with S-IMRT, DO-IMRT is superior in preserving swallowing function.

- DO-IMRT has been proved to have a positive effect on the QOL of HNC patients who received chemo-radiation or radiation alone.

References

- Mendenhall WM, Dziegielewski PT, Pfister DG. DeVita Hellman and Rosenberg’s Cancer Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th edition, Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Cancer of the Head and Neck. 2019; 45.

- Patterson RH, Fischman VG, Wasserman I, Siu J, Shrime MG. Global Burden of Head and Neck Cancer: Economic Consequences, Health, and the Role of Surgery. Otolaryngeal Head Neck Surg. 2020; 162: 296-303.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Attar E, Dey S, Hablas A, Seinfeldian IA, Ramadan M. Head and neck cancer in a developing country: a population-based perspective across 8 years. Oral oncology. 2010; 46: 591-596.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, Haxer MJ, Worden FP, et al. Intensity-modulated chemo radiotherapy aiming to reduce dysphagia in patients with oro-pharyngeal cancer: clinical and functional results. J. Clin Oncol. 2010; 28: 2732–2738.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Barton MB, Jacob S, Shafiq J, Wong K, Thompson SR, et al. Estimating the demand for radiotherapy from the evidence: a review of changes from 2003 to 2012. Radiotherapy Oncol. 2014; 112: 140–144.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Update on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016; 91: 386–396.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Gupta T, Agarwal J, Jain S, Phurailatpam R, Kannan S, et al. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) versus intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a randomized controlled trial. Radiotherapy Oncol. 2012; 104: 343–348.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Fregnani ER, Parahyba CJ, Morais-Faria K, Fonseca FP, Ramos PAM, et al. IMRT delivers lower radiation doses to dental structures than 3DRT in head and neck cancer patients. Radiat Oncol. 2016; 11: 116.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Wu X, Udupa JK, Tong Y, Odhner D, Pednekar GV, et al. AAR-RT - A system for auto-contouring organs at risk on CT images for radiation therapy planning: Principles, design, and large-scale evaluation on head-and-neck and thoracic cancer cases. Medical image analysis. 2019; 54: 45-62.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Simcock R, Simo R. Follow-up and survivorship in head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016; 28: 451-458.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Bhatia A, Burtness B. Human Papillomavirus–Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Defining Risk Groups and Clinical Trials. J. Clin Oncol. 2015; 33: 3243-3250.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Leira J, Maseda A, Lorenzo-Lopez L, Cibeira N, Lopez Lopez R, Lodeiro L, et al. Dysphagia and its association with other health-related risk factors in institutionalized older people: A systematic review. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2023; 110: 104991.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Xu B, Boero IJ, Hwang L, Le QT, Moiseenko V, et al. Aspiration pneumonia after concurrent chemo radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. 2015; 121: 1303-1311.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Brown T, Banks M, Hughes BGM, Lin C, Kenny LM, et al. New radiotherapy techniques do not reduce the need for nutrition intervention in patients with head and neck cancer. Eur J. Clin Nutr. 2015; 69: 1119-1124.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Eisbruch A, Schwartz M, Rasch C, Vineberg K, Damen E, et al. Dysphagia and aspiration after chemo radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: which anatomic structures are affected and can they be spared by IMRT? Int Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004; 60: 1425–1439.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Caglar HB, Tishler RB, Othus M, Burke E, Li Y, et al. Dose to larynx predicts for swallowing complications after intensity modulated radiotherapy. Int J. Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008; 72: 1110–1118.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Batth SS, Caudell JJ, Chen AM. Practical considerations in reducing swallowing dysfunction following concurrent chemo-radiotherapy with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. 2014; 36: 291-298.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- McFarland DH. Netter’s Atlas of Anatomy for Speech, Swallowing, and Hearing: Netter’s Atlas of Anatomy for Speech, Swallowing, and Hearing-E Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2022.

- Christianen ME, Langendijk JA, Westerlaan, van de water TA, Bijl hp. Delineation of organs at risk involved in swallowing for radiotherapy treatment planning. Radiotherapy oncology. 2011; 101: 394-402.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Bisello S, Cilla S, Benini A, Cardano R, Nguyen NP, et al. Dose-Volume Constraints for organs At risk In Radiotherapy (CORSAIR): An "All-in-One" Multicenter-Multidisciplinary Practical Summary.” Current oncology Toronto, Ont. 2022; 29.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Paczona VR, Capala ME, Karancsi BD, Borzási E, Együd Z, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Based Delineation of Organs at Risk in the Head and Neck Region. Advances in Radiation Oncology. 2023; 1: 8: 101042.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Sprave T, Gkika E, Verma V, Grosu AL, Stoian R. Patient reported outcomes based on EQ-5D-5 L questionnaires in head and neck cancer patients: a real-world study. BMC cancer. 2022; 22: 1-1.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Cmelak A, Dietrich MS, Li S, Ridner S, Forastiere A, et al. ECOG-ACRIN 2399: analysis of patient related outcomes after Chemo radiation for locally advanced head and neck Cancer. Cancers of the head & neck. 2020; 5:12.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Vermaire JA, Terhaard CHJ, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Raaijmakers CPJ, Speksnijder CM. Reliability of the 100 mL water swallow test in patients with head and neck cancer and healthy subjects. Head & neck. 2021; 43: 2468–2476.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Mojdami ZD, Watson E, Hope A, de Almeida John R, Howard T, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study on the Effect of Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy on Head and Neck Cancer Patients‟ Quality of Life Using Version 4 of the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. 2023.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaie HM, Sayed SI, Alsini AY, Alkaff HH, Margalani OA, et al. Validity and reliability of an Arabic version of MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI). D 2022; 37: 946-953.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Lee GJ, Lo JY, Das SK, Reiman RE. Knowledge-Based Radiation Therapy Database Optimization on Head and Neck Cancer. Duke University 2015.

- Genovesi D, Perrotti F, Trignani M, Pilla AD, Vinciguerra A, et al. Delineating brachial plexus, cochlea, pharyngeal constrictor muscles and optic chiasm in head and neck radiotherapy: a CT based model atlas. Radiol med. 2015; 120: 352–360.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Tyler J, Bernstein D, Seithel M, Rooney K, Petkar I, et al. Quality assurance of dysphagia-optimized intensity modulated radiotherapy treatment planning for head and neck cancer, Physics and Imaging in Radiation Oncology. 2021; 20: 46–50.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Petkar IS, Bhide K. Newbold, K. Harrington Y, Nutting C. Dysphagia-optimized Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy Techniques in Pharyngeal Cancers: Is Anyone Going to swallow it? Clinical Oncology. 2017; 29: e110ee118.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Der Molen LV, Heemsbergen WD, De Jong R, Van Rossum MA, Smeele LE, et al. Dysphagia and trismus after concomitant chemo-IMRT in advanced head and neck cancer; dose- .effect relationships for swallowing and mastication structures. Radiotherapy oncology. 2013; 364-369.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Levendag PC, Wijers OB, Braaksma MMJ, Boonzaaijer M, Visch LL, et al. Patients with head and neck cancer cured by radiation therapy: a survey of the dry mouth syndrome in long-term survivors. Head Neck. 2002; 24: 737–747.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Nutting C, Finneran L, Roe J, Sydenham MA, Beasley M, et al. Dysphagia optimized intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus standard intensity modulated radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer (DARS): a phase 3, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023; 24: 868-80.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Aaronson NK, et al. Impact of Late Treatment - Related Toxicity on Quality of Life Among Patients With Head and Neck Cancer Treated with Radiotherapy. Journal Of Clinical Oncology. 2008; 26: 3770.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Hutchison AR, Cartmill B, Wall LR, Ward EC. Dysphagia optimized radiotherapy to reduce swallowing dysfunction severity in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer: a systematized scoping review. Head Neck. 2019; 41: 2024-2033.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]

- Carlsson S, Rydén A, Rudberg I, Bove M, Bergquist H, et al. MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck cancer and neurologic swallowing disturbances. Dysphagia 2012; 27: 361–369.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed at]