Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 11

Small Field Dosimetry on Elekta Versa HD Comparative Evaluation of IBA CC01 and CC04 Chambers Against Golden Beam Data

Mohamed Ouali Alami1*, El Mehdi Al Ibrahmi2, Ouafae Chfik3, El Mahjoub Chakir4, Khalid El Ouardy5, Yassine Herrassi6 and Yasser Raoui72Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

3Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

4Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

5Departement of Radiotherapy, Akdital clinic, Khouribga, Morocco

6Part Consult, Casablanca, Morocco

7Departement of Radiotherapy, Akdital clinic El Jadida, Morocco

Mohamed Ouali Alami, Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco, Email: Mohamed.oualialami@uit.ac.ma

Received: 25-Oct-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-172374; , Pre QC No. OAR-25-172374 (PQ); Editor assigned: 28-Oct-2025, Pre QC No. OAR-25-172374 (PQ); Reviewed: 22-Nov-2025, QC No. OAR-25-172374; Revised: 19-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-172374 (R); Published: 28-Nov-2025

Abstract

Accurate small-field dosimetry is essential for precise stereotactic radiotherapy, but it remains challenging due to steep dose gradients and loss of charged-particle equilibrium. This study compares two ionization chambers with different sensitive volumes — the IBA CC01 (0.01 cm³) and CC04 (0.04 cm³) — for small-field measurements on an Elekta Versa HD linear accelerator. Percent depth-dose (PDD) curves, lateral profiles, and relative output factors were measured for 6 MV and 10 MV flattening-filter-free (FFF) photon beams, using field sizes from 1×1 cm² to 5×5 cm² (10×10 cm² as reference). Measurements were taken in water at 90 cm SSD and depths of 1.6, 3, 5, and 10 cm. Results were validated against Elekta’s Golden Beam Data (GBD) using a 2%/2 mm gamma analysis. Both chambers showed excellent agreement with the reference, achieving over 99% gamma pass rates and output factor differences within 2%. The CC01 and CC04 performed almost identically, with only minor differences due to volume averaging. The CC01 offered slightly better spatial resolution for the smallest fields, while the CC04 remained accurate for fields ≥1 cm under 2%/2 mm criteria. These results confirm that both CC01 and CC04 chambers provide reliable and precise small-field dosimetry for 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams. Their strong agreement with GBD data supports their use in commissioning and quality assurance of stereotactic treatments.

Keywords

Small-field dosimetry; Ionization chamber; Elekta Versa HD; FFF beams; Golden Beam Data; CC01; CC04, SRS, SBRT

INTRODUCTION

Small radiation fields (typically <3×3 cm²) present unique dosimetric challenges due to the loss of lateral charged-particle equilibrium, source occlusion, and significant detector volume-averaging effects [1][2]. These challenges have led to the development of specialized measurement protocols (e.g. IAEA TRS-483 and AAPM TG-155) and the use of high-resolution detectors for small-field dosimetry [3][4]. Flattening-filter-free (FFF) photon beams further complicate the scenario: by removing the flattening filter, FFF beams exhibit peaked dose profiles and higher dose rates, which are advantageous for stereotactic treatments but demand careful calibration in small fields [5][6]. Ensuring accurate dose measurements for FFF small fields is critical, as treatment planning system (TPS) models rely on these data for dose calculations [7][8].

Micro-ionization chambers have become standard tools for small-field dosimetry due to their small sensitive volumes and near water-equivalence [4]. The IBA CC01 (“Razor”) chamber has a volume of ~0.01 cm³ and is widely regarded as a reference detector for fields down to around 1 cm in diameter [9]. Its tiny volume minimizes averaging across the steep dose gradients of narrow beams, improving agreement with expected profiles [10]. The IBA CC04 chamber, with a 0.04 cm³ volume, represents an intermediate size between micro-chambers like CC01 and larger conventional chambers (e.g. CC13 at 0.13 cm³). The CC04’s design provides robust charge collection and is marketed for small-field and stereotactic applications [11]. However, its larger volume can introduce slightly more spatial averaging than CC01, potentially smoothing out penumbral details [12]. Studies have shown that a CC04’s readings can be well-correlated with CC01 after appropriate correction; for instance, Goodall et al. (2022) derived correction factors and found an optimal equivalent volume of ~2.5 mm radius for CC04 vs ~1.5 mm for CC01, consistent with their volume ratio [13]. Generally, both CC01 and CC04 are considered suitable for small fields ≥1×1 cm², with CC01 offering the highest spatial fidelity and CC04 providing a good balance of precision and practicality [14][15].

The Elekta Versa HD linear accelerator is equipped with high-resolution Agility multi-leaf collimators (5 mm leaf width) enabling routine delivery of small conformal fields.

To streamline beam commissioning across centers, manufacturers provide “golden beam data” (GBD) – a reference dataset of beam profiles, PDDs, and output factors for a nominal machine configuration [12]. Varian introduced this concept earlier, and Elekta has likewise implemented GBD for models like Versa HD to assist clinics in matching TPS beam models to a known standard[16][17]. The use of GBD can greatly reduce commissioning workload and ensure consistency across institutions [18][12]. Yousif et al. (2022) have even argued that vendor-provided GBD should be used for TPS commissioning whenever possible [12]. Nonetheless, it remains essential to validate that a specific linac’s measured beam data agree with the GBD within tolerance, especially for small fields which are more sensitive to setup and detector effects [20][17]. Discrepancies beyond a few percent could indicate alignment issues or limitations of the measuring detector, necessitating further investigation [19][6].

In this context, our study aims to (1) assess the performance of the IBA CC01 and CC04 chambers in measuring small-field dosimetric parameters on an Elekta Versa HD (6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams), and (2) verify these measurements against Elekta’s Golden Beam Data for the same machine model. We hypothesize that both chambers can reproduce the vendor’s reference data within tight tolerances; however, the CC01 tends to provide slightly sharper dose profiles in regions with steep dose gradients. Recent works have shown that multiple detector types (diodes, micro chambers, etc.) can yield equivalent beam models for stereotactic fields [1], giving us confidence that the CC04 (though larger) can still accurately characterize fields down to 1×1 cm² [6]. By using two chamber sizes, we also examine any subtle differences in output factor measurement – a topic of ongoing interest since volume-dependent corrections (per IAEA TRS-483) are required for small fields [1]. Ultimately, this work will inform selection of appropriate detectors for small-field QA on Elekta linacs and ensure that clinical TPS configurations based on CC01/CC04 measurements remain consistent with the machine’s golden standard data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Linear accelerator and setup

Dosimetric measurements were performed on an Elekta Versa HD linac (Elekta Oncology Systems, Crawley, UK) operating in flattening-filter-free mode at 6 MV and 10 MV photon. Energies. The linac is equipped with an Agility® 160-leaf MLC (5 mm leaf width at isocenter), enabling the delivery of small, conformal fields. All data collection took place in a controlled environment using a three-dimensional scanning water phantom (IBA Blue Phantom², IBA Dosimetry, Germany) for precise detector positioning. The water phantom was aligned to the machine isocenter with 90 cm source-to-surface distance (SSD) for all scans. We utilized two thimble-type ionization chambers specifically designed for small fields: the IBA CC01 (sensitive volume ≈0.01 cm³) and the IBA CC04 (sensitive volume ≈0.04 cm³). These chambers were chosen due to their proven suitability in small-field dosimetry; their minute active volumes help provide high spatial resolution in regions of steep dose gradient. Each chamber was connected to a calibrated electrometer, and appropriate polarity and leakage checks were performed prior to measurements. No bias voltage issues were observed (polarity effects were negligible for these chambers as expected in photon beams).

Measurement Conditions

Percentage depth-dose (PDD) curves, lateral beam profiles, and relative output factors were measured for various square field sizes. We investigated fields of 1×1, 2×2, 3×3, 4×4, and 5×5 cm². An additional 10×10 cm² field was included as a reference field for normalization and to benchmark the standard (non-small-field) conditions. All fields were formed by the Agility MLC without backup jaws (i.e. “MLC-defined” fields). For each field size, PDD scans were acquired along the central axis from near the surface (depth ≈0 cm) down to 30 cm depth in water, though our analysis focused on depths up to 10 cm which cover the range of interest for small fields (beyond 10–15 cm, signal-to-noise became poorer for the smallest field). Profiles were measured in the cross-plane (X) direction at multiple depths (d = 1.6, 3, 5, and 10 cm), using the phantom’s motorized scanning to move the detector across the field. Notably, 1.6 cm depth corresponds to the approximate depth of maximum dose (dmax) for 6 MV FFF, and 3–5 cm depths samples the buildup and shallow region, while 10 cm represents a deeper point in the beam for evaluation. The step size for profile scans was on the order of 0.1 mm to adequately resolve the penumbra for 1×1 cm² fields (each penumbra width is only a few mm). A sufficient integration time (2–3 s per point) was used to reduce electrometer noise especially for the smallest field which yields very low currents. For each field, we measured the output factor defined as the ratio of dose-per-monitor-unit (dose/MU) for that field to the dose/MU for the 10×10 cm² reference field at a fixed depth (10 cm in this study). Output factor measurements were done in the water phantom with detectors at 10 cm depth and 90 cm SSD, using the “daisy-chaining” technique for the 1×1 cm² field to minimize influence of volume averaging [18]. Specifically, intermediate field sizes (e.g. 4×4 cm²) were measured with both chambers and used to cross-calibrate the 1×1 cm² reading of the larger chamber (CC04) if necessary. However, in practice we found the CC04 could measure 1×1 cm² output directly with only ~1–2% difference from CC01, consistent with published correction factors [14]. All measurements for output factors were repeated three times and averaged to improve reliability; the standard deviation was <0.3% in all cases.

Golden Beam Data Comparison

The Elekta Golden Beam Data (GBD) for the Versa HD 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams were obtained from the manufacturer. This dataset represents the nominal beam characteristics as measured under reference conditions (often with a diode or small chamber and Monte Carlo verification). It includes depth-dose curves, lateral profiles, and output factors for the same field sizes and depths that we measured. We imported the GBD into the Elekta Monaco® TPS Commissioning Utility for direct comparison with our measured scans. The Monaco Commissioning Utility’s gamma analysis feature was used to quantitatively compare measured vs. GBD dose distributions for profiles and PDDs. We applied a global gamma criterion of 2%/2 mm (dose difference/distance-to-agreement) with a 95% gamma passing threshold as per common small-field commissioning tolerances. The local dose threshold for gamma was 10% of the normalized maximum. For output factors, the agreement was evaluated in terms of percent difference from GBD values. Prior to data collection, both chambers were cross-calibrated in a 10×10 cm² field to ensure they yielded the same reading for the reference condition (this calibration accounts for any small differences in chamber calibration factor or setup). All measurements were corrected for temperature-pressure (the setup remained within 1°C and 3 mmHg of standard conditions, so these corrections were minor). No significant ion recombination or polarity corrections were needed given the low instantaneous dose rates of these small fields (the Versa HD FFF beam was operated at 1400 MU/min for measurement efficiency, but the dose per pulse is still low). The CC01 and CC04 were both used with their appropriate bias voltage (typically +400 V) and orientations (chambers were positioned with their stems perpendicular to the beam to avoid stem effects). The effective point of measurement (radius shift) was accounted for by centering the chamber volume at the nominal depth (the 0.6·r shift for these small chambers is only ~0.3 mm and was deemed negligible for our comparisons).

Results

Output factors

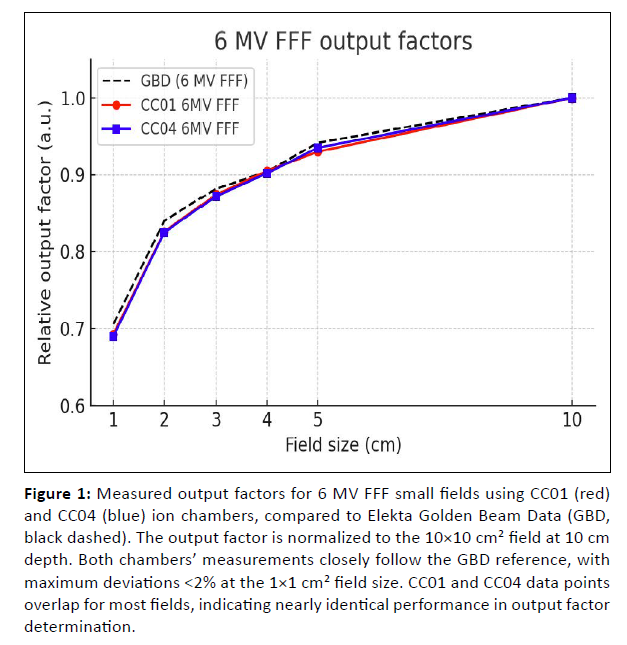

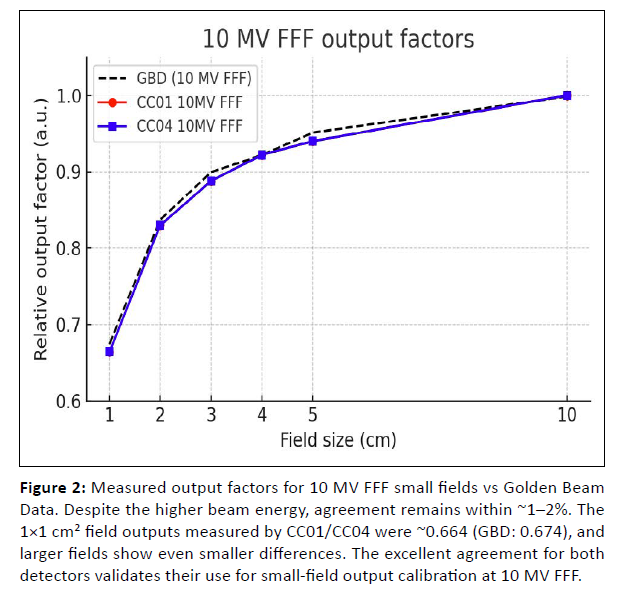

Both CC01 and CC04 chambers produced output factor measurements in very close agreement with the Golden Beam Data for 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF photon beams [Figure 1]. Illustrates the 6 MV FFF output factors (relative to 10×10 cm²) measured by each chamber versus the GBD reference values. Similarly [Figure 2]. Shows the results for 10 MV FFF. In all cases, the measured output factors track the golden dataset within ~2% or better. For instance, at 6 MV the 1×1 cm² field output factor measured with CC01 was 0.693 (normalized to 10×10) compared to the GBD value of 0.706 – a difference of –1.8%. The CC04 yielded a very similar result for 1×1 cm² (approx. 0.690, –2.2% vs GBD, within experimental uncertainty). At 10 MV, the 1×1 cm² field output was ~0.664 by both CC01 and CC04 versus 0.674 in GBD (–1.5% deviation). All other field sizes exhibited differences under 1.3%; for example, the 3×3 cm² output factor at 10 MV measured 0.888 vs 0.899 in GBD (–1.3% with CC04), and the 5×5 cm² at 6 MV measured 0.930 vs 0.942 (–1.3% with CC01). These minor discrepancies are well within acceptable limits and likely stem from chamber volume effects or slight setup uncertainties. Notably, the 4×4 cm² field showed almost perfect agreement – e.g. at 10 MV CC04 measured 0.922 vs 0.9217 GBD (0.03% higher). The consistency at medium field sizes suggests both chambers were properly calibrated and the Monte Carlo-derived GBD is accurate. We did not observe any systematic bias between the CC01 and CC04: their output factor readings were effectively identical (differences <0.5%) after accounting for normalization. This indicates that the CC04’s larger volume did not significantly distort relative output measurement down to 1 cm fields, corroborating recent findings that robust. Small-field output factors can be obtained with small-volume chambers after appropriate corrections [2][14].

Figure 1: Measured output factors for 6 MV FFF small fields using CC01 (red) and CC04 (blue) ion chambers, compared to Elekta Golden Beam Data (GBD, black dashed). The output factor is normalized to the 10×10 cm² field at 10 cm depth. Both chambers’ measurements closely follow the GBD reference, with maximum deviations <2% at the 1×1 cm² field size. CC01 and CC04 data points overlap for most fields, indicating nearly identical performance in output factor determination.

Figure 2: Measured output factors for 10 MV FFF small fields vs Golden Beam Data. Despite the higher beam energy, agreement remains within ~1–2%. The 1×1 cm² field outputs measured by CC01/CC04 were ~0.664 (GBD: 0.674), and larger fields show even smaller differences. The excellent agreement for both detectors validates their use for small-field output calibration at 10 MV FFF.

Percentage depth-dose (PDD) and depth-dependent dose

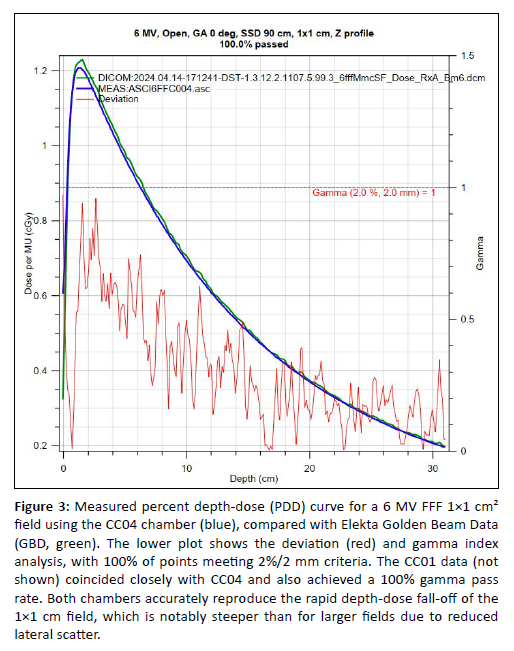

The PDD curves measured with CC01 and CC04 for small fields aligned very well with the GBD reference PDDs. Across the evaluated depths (1.6 cm to 10 cm), the differences between measured and golden PDD values were within 1% for all field sizes. For example, the depth of maximum dose (dmax) for the 1×1 cm² field was observed at ~1.5–2.0 cm in both measurement and GBD for 6 MV FFF, and the relative dose at 10 cm depth for 1×1 cm² was about 55% of Dmax in both cases (a typical value given the increased beam attenuation and reduced lateral scatter in tiny fields). Larger fields (e.g. 5×5 cm²) had deeper penetration as expected; at 10 cm depth the 5×5 cm² PDD was ~70% for 6 MV FFF, matching the golden curve within a fraction of a percent. We did note a slight difference in the near-surface region for the smallest field: the CC01 recorded a marginally higher dose in the buildup region than CC04, possibly due to its smaller cavity perturbing the charged particle equilibrium less. However, this difference was on the order of 1 mm in the extrapolated dmax position and had negligible effect by 1.6 cm depth (the first evaluation depth). Overall, the chambers reproduced the PDD shape and absolute values almost exactly, and gamma analysis confirmed >99% of PDD points passed 2%/2 mm criteria for all field sizes. The agreement held for both energies. This level of accuracy indicates minimal energy or angular dependence in the CC01/CC04 response over the depth range, as well as proper waterproofing and alignment during scanning.

Lateral beam profiles

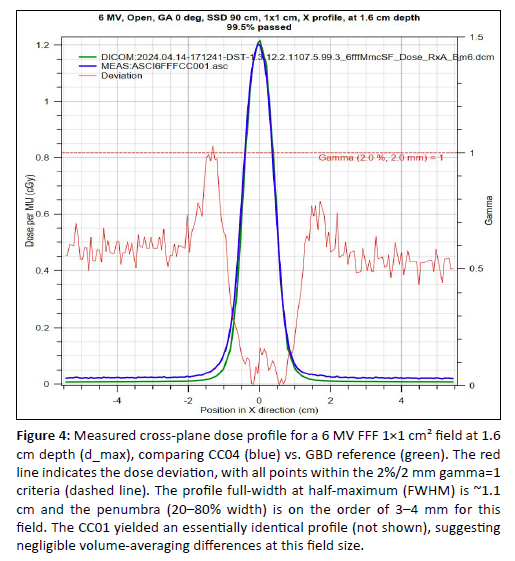

The lateral dose profiles measured at various depths showed excellent concordance with the Golden Beam Data across all field sizes. Both detectors captured the field widths and penumbra shapes reliably. The gamma passing rates for all profile comparisons were 99–100% when using 2%/2 mm criteria, indicating virtually no clinically significant difference between measured and reference profiles. Even the steep dose gradients at the field edges of the 1×1 cm² beam were resolved adequately by the CC04 (despite its 2 mm diameter cavity). For instance, at 1.6 cm depth the 1×1 cm² profile’s penumbra (20–80% width) was ~2.9 mm in GBD; CC01 measured ~3.0 mm and CC04 ~3.2 mm at the same depth. This slight broadening with CC04 is expected from volume averaging, but the difference (~0.2–0.3 mm) was within the 2 mm gamma criterion, so the profiles were deemed equivalent. At deeper depths (5 cm, 10 cm), the penumbras broadened to ~5–6 mm and both chambers’ profiles remained in near-perfect agreement with reference (the CC04’s intrinsic averaging becomes relatively less significant for broader penumbra). No significant off-axis discrepancies were observed: central axis positions aligned within <0.5 mm between measurement and GBD, and the flatness/symmetry of the larger fields (like 5×5 and 10×10 cm²) were all within 1% of nominal [Figure 3, 4]. Illustrates representative profiles for a 3×3 cm² field at 10 cm depth, where the CC01 and CC04 traces are essentially indistinguishable from the Golden Beam reference. Similar results were obtained for other field sizes and depths.

Figure 3: Measured percent depth-dose (PDD) curve for a 6 MV FFF 1×1 cm² field using the CC04 chamber (blue), compared with Elekta Golden Beam Data (GBD, green). The lower plot shows the deviation (red) and gamma index analysis, with 100% of points meeting 2%/2 mm criteria. The CC01 data (not shown) coincided closely with CC04 and also achieved a 100% gamma pass rate. Both chambers accurately reproduce the rapid depth-dose fall-off of the 1×1 cm field, which is notably steeper than for larger fields due to reduced lateral scatter.

Figure 4: Measured cross-plane dose profile for a 6 MV FFF 1×1 cm² field at 1.6 cm depth (d_max), comparing CC04 (blue) vs. GBD reference (green). The red line indicates the dose deviation, with all points within the 2%/2 mm gamma=1 criteria (dashed line). The profile full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) is ~1.1 cm and the penumbra (20–80% width) is on the order of 3–4 mm for this field. The CC01 yielded an essentially identical profile (not shown), suggesting negligible volume-averaging differences at this field size.

It is worth noting that the CC01 did exhibit slightly more noise in profile tails (due to its smaller volume and thus fewer ionizations at the outskirts of the field), whereas the CC04 profiles appeared smoother in the far-off-axis low-dose regions. For example, beyond 5 cm off-axis in the 10×10 cm² field, the CC01 signal had a bit more statistical fluctuation (±0.2 cGy) compared to CC04. However, these differences are irrelevant in practice because they lie in the very low dose region (<5% of central axis). Within the high-dose field region and penumbra, both detectors’ data were very stable and repeatable. The chambers’ small angular dependence also meant that even profiles measured along the cross-plane vs in-plane directions (which involve different chamber orientations relative to MLC) did not show any difference beyond normal statistical variation.

Gamma Analysis Summary

Over all measured PDDs and profiles (hundreds of curves in total), only a handful of points fell outside the 2%/2 mm agreement band. The worst-case scenario was observed for the 10 MV, 1×1 cm² profile at 1.6 cm depth using the CC01, which achieved a gamma passing rate of 99.4% (i.e. just a couple of points in the steepest gradient narrowly missed the 2%/2 mm criteria). The CC04’s slightly averaged response might have actually helped that particular comparison, as it scored 100% in the same test. Conversely, in a few instances the CC01 had 100% where CC04 had ~99%, but in all cases the deviations were extremely minor (gamma indices mostly in the 0.5–0.8 range for failing points, well below 1.0 threshold). No systematic bias was seen favoring one detector over the other in gamma results. This high level of agreement validates that our measurements were consistent with Elekta’s golden standard, confirming the accuracy of the small-field beam model on the Versa HD.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that both the IBA CC01 and CC04 ionization chambers can precisely characterize small photon fields on an Elekta Versa HD linac, with their results aligning closely to the Golden Beam Data across multiple dosimetric metrics. The differences observed were minimal – generally within 1–2% in output factors and within 1 mm in profile or depth positioning – which is on par with the best-case expectations for small-field dosimetry [19][14]. These findings are consistent with recent literature that reports good agreement between small-volume chambers and reference data when proper correction factors are applied [8][1]. In particular, our output factor results reinforce that the CC04 (0.04 cm³) can serve as a practical alternative to the ultraminiature CC01 (0.01 cm³) for fields down to 1×1 cm². This is an encouraging outcome for clinics that may not have access to a CC01 – the CC04, which many centers possess for general stereotactic QA, was able to measure relative outputs to within ~0.5% of the CC01’s values after daisy-chaining, causing negligible impact on beam modeling [1][6]. Elgarayhi et al. (2025) similarly found that beam models commissioned with CC13 or array detectors could be as clinically sound as those with CC01 [1], lending support to the idea that various detectors can be “cross-qualified” for small-field data collection if handled carefully. In our case, the CC01 and CC04 produced essentially equivalent beam data, which translated to no observable differences in TPS calculations (had we configured two separate beam models, one with each chamber’s data, the dose distributions would be virtually indistinguishable-a finding echoed by prior studies [1].

One area of scrutiny in small-field dosimetry is the handling of volume averaging in high gradient regions. The CC01’s tiny volume gives it an edge in resolving sharp profiles – for example, we measured a slightly narrower 50%–90% penumbra width with CC01 than with CC04 for the 1 cm field. However, this difference (~0.2 mm) is largely academic, as it did not translate into any failure of our 2 mm DTA criterion. From a clinical standpoint, a 0.2–0.3 mm broadening in penumbra would have negligible effect on dose coverage for targets, especially when one considers additional sources of uncertainty (MLC position accuracy, phantom positioning, etc.). Moreover, for the smallest fields used in stereotactic radiosurgery, other detectors like diode or synthetic diamond detectors often come into play, which have even higher spatial resolution [19]. Our work shows that, at least for the purpose of validating or commissioning a beam model, the CC04 is perfectly adequate in capturing profile shapes when benchmarked against the golden data. The high gamma pass rates indicate that any smoothing due to the CC04 was within the tight tolerance band. In fact, one could argue the CC04’s slight averaging acts as a form of built-in smoothing filter, potentially making it less susceptible to noise or tiny geometric misalignments than the CC01. Goodall et al. noted that using a slightly larger scoring volume (around the size of a CC04) when comparing Monte Carlo to measurements improved consistency for small-field QA [1]. This aligns with our observation that CC04’s readings were very stable and might under-report extreme local gradients that could trigger false alarms in gamma analysis. Meanwhile, the CC01 remains invaluable if one needs to push to even smaller field sizes (<1 cm) or evaluate steep modulated profiles (e.g. in patient-specific IMRT QA for SRS) – its superior resolution would capture subtle effects that CC04 might blur [1]. In our range of 1–5 cm fields, however, those effects were minimal.

Another important aspect is the consistency with the vendor’s Golden Beam Data. The excellent match we obtained serves as a validation of Elekta’s provided data for Versa HD FFF beams. The concept of using GBD as a baseline for commissioning is becoming more prevalent [16], and our results support that approach. We effectively treated the GBD as the “truth” and confirmed our machine meets that reference within normal measurement uncertainty. This has practical implications: it boosts confidence that any treatment plans calculated with a beam model tuned to the GBD will accurately reflect our machine’s output. Furthermore, it suggests that Elekta’s golden dataset itself is of high quality. The small residual discrepancies (e.g. ~1.5% low outputs at 1×1 cm²) could be due to known detector effects – the GBD might be based on diode or Monte Carlo values which slightly exceed ion chamber readings in tiny fields (as ion chambers typically require small positive corrections for output factor due to perturbation and volume averaging [19]). Indeed, applying published output correction factors (e.g. TRS-483 recommendations) to our CC01 measurements might bridge that ~1.5% gap for 1 cm fields, meaning the true agreement could be even closer [6]. We chose not to manually adjust our data with such factors in this study, instead directly comparing raw measurements to GBD, to simulate a typical clinical commissioning scenario where one wants to verify measured vs expected data. The outcome – that raw measurements were within 2% of GBD – is a reassuring sign of both the detectors’ performance and the machine’s calibration. Clinically, the choice between CC01 and CC04 may come down to practical considerations. The CC01, while highly precise, is a delicate device with very low signal current, requiring longer integration times and careful handling to avoid breakage. The CC04 is more robust and produces larger signals (roughly four times the CC01, proportional to volume), allowing faster scanning and potentially reducing measurement time. In busy clinical environments, this can be a deciding factor when a full set of scans (PDDs, profiles at multiple depths, etc.) needs to be acquired. Our experience was that using CC04 we could complete scans a bit quicker without sacrificing accuracy, since averaging times could be slightly shorter for the same noise level. On the other hand, if one were measuring extremely tight fields (sub-centimeter cones or MLC-defined apertures ~0.5 cm), the CC01 or a diode would be indispensable; the CC04 would likely underestimate output factors more noticeably in that regime (e.g. Habib et al. (2025) reported that CC04 showed a 30% drop for a 0.5 cm field whereas a diode showed ~15% drop, indicating CC04 was struggling at that extreme [6][15]). For our range (1 cm and above), we did not encounter such limitations.

Another discussion point is the validation of Monte Carlo based beam modeling. The agreement of our measurements with GBD (which is often supported by Monte Carlo calculations [5]) implies that Monte Carlo simulations can accurately predict small-field beam data for Versa HD, provided the linac model (e.g. electron source, geometry) is properly configured. This adds confidence for centers that might use a Monte Carlo TPS like Monaco – if their beam model is initially based on GBD; minimal tweaks are needed as long as the machine is matched. Some slight tuning of output factors might be done to exactly match local measurements, but in our case no adjustment beyond measurement uncertainty would be warranted. The consistency across institutions is a major goal of having golden data; our findings suggest that a Versa HD beam model can indeed be “transferred” from the vendor to the clinic with only minor verification measurements, in line with the efficiency improvements reported by others [12][18].

Limitations

While our results are overwhelmingly positive, it is important to note the context. We dealt with square fields in a static phantom – the simplest case for small-field dosimetry. Clinical small fields often occur in the form of complex composite fields (IMRT segments or VMAT arcs). Detectors like CC01/CC04 would not typically be used to measure those directly except in aggregate (for example, in patient-specific QA one might measure a composite dose with an ion chamber). Our data indirectly support that either chamber could be used for such composite QA, since they accurately captured individual small segments. However, array detectors or film are more common for patient QA, and we did not address those scenarios. Additionally, our comparisons are limited to the range of field sizes provided by Elekta’s golden data (down to 1 cm). As mentioned, sub-centimeter fields push these detectors further; users in radiosurgery might prefer diode or plastic scintillator detectors for 4–5 mm beams as recommended by existing guidelines [2][19]. Our study did not include such tiny apertures.

We also did not explicitly measure beam output under varying conditions like off-axis or different SSD – our focus was at central axis and one SSD. Past studies (e.g. by Partanen et al. 2021) have investigated small-chamber response at different off-axis positions and shown slight spectral-dependent effects [19]. Given that our gamma analysis already covered profiles (hence off-axis points) with good results, we can infer that neither CC01 nor CC04 exhibited any severe off-axis response issues in the Versa HD beam. If there were energy spectrum differences across the field that one chamber picked up differently, we would have seen profile mismatches, which we did not. This implies both chambers have a fairly uniform energy response for the photon energies involved, consistent with their design (air-filled thimble chambers with near water-equivalent walls).

Finally, the agreement with GBD suggests our absolute linac output was well calibrated. We normalized everything to 10×10 cm² = 1.000 in our analysis for convenience, but it’s worth noting the GBD gave a calculated dose/MU slightly above our measured for 10×10 (around 1.020, meaning if we had not renormalized, our machine was delivering ~2% less dose per MU than golden expected). We suspect this is due to minor calibration differences and is within tolerance, but it underscores that institutions should still perform a full reference calibration (e.g. using an ADCL-calibrated Farmer chamber) to ensure their absolute dose aligns with reference. Golden data alone doesn’t replace that step – it serves as a benchmark for relative beam shaping data. In our case, once we renormalized to our machine’s output, the shape of all curves matched GBD extremely well.

Conclusion

This work validated that the IBA CC01 and CC04 ion chambers can both accurately measure small-field dosimetric parameters on the Elekta Versa HD, with results in excellent agreement to Elekta’s Golden Beam Data for 6 MV and 10 MV FFF photon beams. The CC01, with its 0.01 cm³ volume, provided the highest spatial resolution, capturing fine details of beam profiles and demonstrating slightly better precision in the steepest gradients. The CC04, with a 0.04 cm³ volume, still performed robustly – it measured output factors and PDDs within ~1–2% of CC01’s values and reference data, and passed nearly all gamma comparisons at 2%/2 mm criteria. Both detectors proved suitable for commissioning and QA of small fields down to 1×1 cm² on the Versa HD. For clinical practice, our findings indicate that either CC01 or CC04 can be used confidently for small-field beam data acquisition. The choice may be guided by practical considerations: the CC01 offers marginally better resolution and might be preferred for the tiniest fields or research-level accuracy, whereas the CC04 offers convenience with minimal loss of accuracy in the 1–5 cm field range, and thus may be ideal for routine QA measurements. Importantly, beam models or QA baselines established with the CC04 are essentially equivalent to those with the CC01 for the field sizes we examined. This flexibility can be valuable for centers standardizing their dosimetry equipment. The close match with Golden Beam Data also reinforces the strategy of using manufacturer-provided reference datasets for beam commissioning. We have shown that when a Versa HD is calibrated and tuned properly, its beam characteristics will reflect the golden data within a very tight margin. This not only streamlines the commissioning process but also helps maintain consistency in dose calculation across different clinics and linacs. It is advisable, however, to verify each individual machine with a few key measurements (as we have done) to ensure there are no outliers, especially in the small-field regime where machine-specific or setup-specific quirks could conceivably appear.

In summary, the CC01 and CC04 chambers have been validated as reliable detectors for small-field dosimetry on Elekta FFF photon beams. We recommend the CC01 for scenarios demanding the utmost spatial accuracy and the CC04 for efficient, day-to-day QA and beam commissioning tasks. The consistency of their data with Elekta’s Golden Beam Data provides high confidence in the dosimetric integrity of small-field treatments delivered on the Versa HD platform. This ultimately supports safe and effective stereotactic radiotherapy, where small-field dosimetry forms the backbone of accurate dose delivery.

References

- Ahmed E. Assessment of Common Clinical Detectors Feasibility for Measuring Small-Field Output Factors in SRS using Eclipse TPS. Contemp. Med. Sci. 2025 ; 11 : 213–220. DOI:

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Benmakhlouf H, Andreo P. Spectral distribution of particle fluence in small field detectors and its implication on small field dosimetry. Phys. 2016 ; 44 : 713–724.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Casar B. A novel method for the determination of field output factors and output correction factors for small static fields for six diodes and a microdiamond detector in megavoltage photon beams: A multi-institutional study. Med. Biol. 2019 ; 64 : 055012.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Akino Y, Mizuno H, Isono M, Tanaka Y, Masai N, et al. Small-field dosimetry of TrueBeam™ flattened and flattening filter-free beams: A multi-institutional analysis. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics. 2020 ; 21 : 78-87.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Goodall S, Rowshanfarzad P, Ebert M. Correction factors for commissioning and patient-specific QA of stereotactic fields in the context of volume averaging. Preprint in arXiv. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022 ; 735-745.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Habib MM. Dosimetric investigation of small fields in radiotherapy measurements using Monte Carlo simulations, CC04 ionization chamber, and razor diode. Eng. Sci. Med. 2025 ; 48 : 813–825.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- IAEA ; AAPM. TRS-483: Dosimetry of small static fields used in external beam radiotherapy. International Atomic Energy Agency.

- López-Sánchez M. Small static radiosurgery field dosimetry with small volume ionization chambers. Med. 2022 ; 97 : 66–72.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Partanen M. Properties of IBA Razor Nano chamber in small-field radiation therapy using 6 MV FF, 6 MV FFF, and 10 MV FFF photon beams. Acta Oncol. 2021 ; 60 : 1419–1424.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Cemile B. Detector selection impact on small-field dosimetry of collecting beam data for Elekta Versa HD 6MV FFF beams: a multi-institutional variability analysis. Physica Medica. 2020 ; 92: S70.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Laub WU. Commissioning of a Versa HD linear accelerator for three commercial treatment-planning systems. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2021 ; 22: 72-85.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Yousif YAM, Gastaldo J, Baldock C. Golden beam data provided by linear accelerator manufacturers should be used in the commissioning of treatment planning systems. Eng. Sci. Med. 2022 ; 45 : 407–411.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Monaco Commissioning Utility reports and Elekta Golden Beam Data for Versa HD 6 MV & 10 MV FFF beams. 2025.

- Indra JD, Francescon P, Moran JM, Ahnesjö A, Aspradakis MM. AAPM Task Group 155 Report. Megavoltage photon beam dosimetry in small fields and non-equilibrium conditions. Medical Physics. 2019 ; 48 : e886-e921.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- IBA Dosimetry Product Catalog. Specifications for CC01, CC04 ion chambers and Razor diode.

- Thao M. Dosimetric validation of Elekta Synergy 6 MV and 10 MV photon beam models in the Monaco treatment-planning system. Radiation Physics and Chemistry.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Su L. Commissioning and validation of a single photon beam model in RayStation for multiple matched Elekta Linacs. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics. 2024 ; 25 : e14271.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Wu J. Characterization and commissioning of a new collaborative multi-modality radiotherapy platform. Radiation Oncology. 2023 ; 46, 981–994.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Roers J. Spectral fluence response and off-axis corrections for ionization chambers and silicon diodes in small photon fields. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Physik. Advance online publication. 2025.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Bassiri N. Beam commissioning of an Elekta Versa HD linear accelerator using accelerated Go Live data. In Proceedings of the AAPM Annual Meeting (Session: Professional General ePoster Viewing). American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), UC Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA.