Research Article - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 11

Evaluation of the impact of slice thickness on CT and Cone Beam CT image quality in radiotherapy

Amine El Outmani1,2*, M Zerfaoui1, I Hattal1,2, A Rrhioua1, D Bakari3, Y Oulhouq4 and K Bahhous52Centre Oriental Al Kindy, Oncology et diagnostic du Maroc (ODM), Oujda, Morocco

3National School of Applied Sciences, University Mohammed First, Oujda, Morocco

4National Institute for Research in Nuclear Physics and its Applications, Oujda, Morocco

5Faculty of Medicine and pharmacy, Mohammed First University, Oujda, Morocco

Amine El Outmani, LPMR FSO Mohammed First University, Faculty of Sciences, LPMR, 60000, Oujda, Morocco, Email: am.eloutmani@ump.ac.ma

Received: 07-Oct-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-171673; , Pre QC No. OAR-25-171673 (PQ); Editor assigned: 10-Oct-2025, Pre QC No. OAR-25-171673 (PQ); Reviewed: 22-Oct-2025, QC No. OAR-25-171673; Revised: 03-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-171673 (R); Published: 28-Nov-2025

Abstract

Objective: This study evaluates the accuracy of slice thickness and its impact on CT and Cone Beam CT (CBCT) image quality and dose distribution in radiotherapy. Materials and Methods: The Catphan 604 phantom was scanned using a CT scanner and a linear accelerator On-Board Imager. Images were acquired at 1, 3, and 5 mm slice thicknesses to assess the effects on low-contrast resolution, Hounsfield Unit (HU), Modulation Transfer Function (MTF), uniformity, and Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR). Analysis and dose calculation were performed using Pylinac and Eclipse, respectively. Results: Greater measurement errors were detected for CBCT slice thickness compared to CT. Thinner slices improved resolution but increased noise, whereas thicker slices reduced noise but compromised detail. CT outperformed CBCT in terms of resolution, HU accuracy, uniformity, and CNR. Slice thickness had no significant effect on dose distribution, but differences were noted in bone structures between the modalities. Conclusion: Slice thickness significantly affects CT and CBCT image quality. Its verification is essential for optimizing radiotherapy imaging protocols.

Keywords

CT; CBCT; Slice Thickness; Image Quality; Radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Computed Tomography (CT) scanning and Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) have transformed radiotherapy (RT) and medical imaging [1]. These imaging modalities are essential components of clinical workflows and are of critical importance in diagnosis and treatment planning [2]. CT and CBCT images are directly related to the diagnostic interpretation and accuracy of RT treatment [3]. In the field of RT, clear visualization of tumors and surrounding tissues is critical to ensure that radiation is delivered precisely and carefully [4].

Slice thickness is one of the most important factors in determining overall image quality. This parameter has a direct impact on the level of detail encoded in the cross-sectional images and, subsequently, the resolvability of anatomical structures and the fidelity of imaging features [5]. Finding the best slice thickness is important for image quality, which assists in accurate treatment planning [6-8].

The American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) has established guidelines for slice thickness in RT imaging. For three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT), AAPM allows slice thicknesses of up to 5 mm [9], while recommending 3 mm for Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT) and Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT) [10]. For Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) and Stereotactic Radiotherapy (SRT), which demand the highest precision, AAPM suggests a maximum slice thickness of 1 mm [11]. These recommendations are aimed at fine-tuning the slice thickness to confirm the accuracy and efficacy of different RT techniques.

Evaluating and optimizing slice thickness in clinical practice can be challenging owing to limitations in proprietary software and the availability of tools for image quality analysis. Open-source tools represent a good solution, providing flexible and low-cost means of evaluating imaging parameters. These tools allow clinicians and researchers to examine the effects of slice thickness on image quality, which can improve the accuracy and effectiveness of RT.

This study introduced an open-source tool specifically designed to assess the effects of slice thickness on image quality parameters in both CT and CBCT. The methodology aims to compare various image parameters across different slice thicknesses to determine the optimal balance between preserving essential image details and avoiding unnecessary noise that could degrade image quality. Additionally, the study included a dosimetric analysis comparing dose distributions across various slice thicknesses and between the two imaging techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Catphan 604

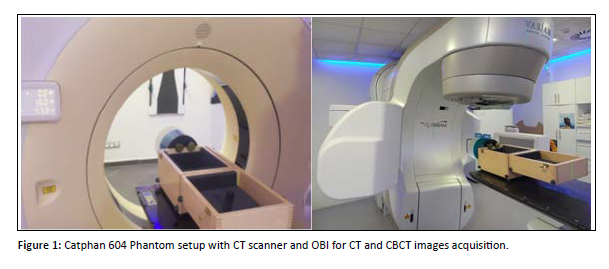

For this study, we employed the Philips Brilliance Big Bore CT scanner and On-Board Imager (OBI) of the Varian Vital beam linear accelerator. Images of the Catphan 604 phantom [12], which contains inserts representing the components of human tissue from the air cavities to the bone, were obtained using a CT scanner. CBCT images were obtained using the OBI device [Figure 1]. The measurements were performed for images acquired using the CT head and neck imaging protocol and the CBCT head and neck protocol. Catphan 604 contains four modules: CTP732: Resolution Geometry Module; CTP682: Sensitometer (CT Number Linearity) Module, CTP730 Low-Contrast Module, and CTP729: Uniformity Module. Both CT and CBCT modalities were used to scan the phantom and the obtained data were analyzed to assess the effect of slice thickness on the image quality in the respective systems.

Figure 1: Catphan 604 Phantom setup with CT scanner and OBI for CT and CBCT images acquisition.

Pylinac

Images of the Catphan 604 phantom were analyzed using the open-source Python library Pylinac (version 3.25.0) [13], which analyze imaging systems for RT quality assurance (QA). This robust tool facilitates the analysis of datasets and images and can process raw data or images as input data to generate outputs in the form of numerical values, PDFs, graphical, and visualization reports. Pylinac allows medical physicists to quickly confirm that their therapy equipment is working correctly and safely, freeing up precious time and resources in QA workflow. In this study, the relevant Pylinac modules were used for CT and CBCT image analyses. The following parameters were analyzed: slice thickness, Low-Contrast Resolution, Hounsfield Unit (HU), Modulation Transfer Function (MTF), Uniformity and Contrast-to-Noise Ratio.

Slice thickness

Slice thickness is an important parameter because it directly affects the partial volume effect, which occurs when a voxel encompasses different tissues. This can compromise image accuracy and, therefore, treatment precision, especially for small or complicated target volumes such as tumors. In this study, slice thickness was measured at the center of the Field Of View (FOV) as the distance between two points at half the maximum height of the slice profile along the axis of rotation, using the Catphan 604 phantom and Pylinac software.

Low-Contrast Resolution

A low-contrast resolution indicates the system's ability to differentiate between areas with low-density varia-tions. Good low-contrast resolution is particularly important in RT, where accurate delineation of organs at risk and target volumes is the first step for accurate treatment delivery. In this study, the CTP730 module of Catphan 604 was used to measure the low-contrast resolution

Hounsfield Unit (HU)

The critical importance of consistent and reliable Hounsfield Unit (HU) values in RT lies in their role in dose calculation. Improving the HU accuracy in treatment planning maximizes patient benefits. To measure HU in CT and CBCT and identify the difference between the two, the Catphan 604 sensitometry module (CTP682), specifically designed to verify the HU accuracy, was used.

Modulation Transfer Function (MTF)

The modulated transfer function (MTF) is a crucial parameter that indicates the capacity of an imaging system to reproduce fine details while preserving the contrast. In this study, high-resolution inserts of the Catphan 604 phantom were used to evaluate how well the system resolved fine structures under varying contrast conditions. The MTF curves were generated using Pylinac software.

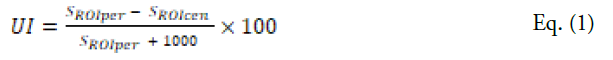

Uniformity

The Uniformity Index (UI) measures the disparity in Hounsfield Unit (HU) values between the peripheral and central Region Of Interest (ROI )of CT or CBCT images and is a crucial tool for evaluating spatial uniformity. It is defined as.

Where:

UI: uniformity index

SROIper is the HU value in the peripheral region of interest (ROI) of the image.

SROIcen is the HU value in the central region of interest (ROI) of the image.

Hounsfield Units (HUs) were measured in the homogeneous region to evaluate deviations across the different zones of the image (top, bottom, right, left, and center) [Figure 2]. A Region of Interest (ROI) with a diameter of 5 mm was selected for the measurements.

Figure 2: Measurement of uniformity on a CT and CBCT images using the CTP729 module.

A negative UI value indicates a capping artifact, whereas a positive value indicates a cupping artifact. Values near zero indicate a uniform image with minimal artifacts.

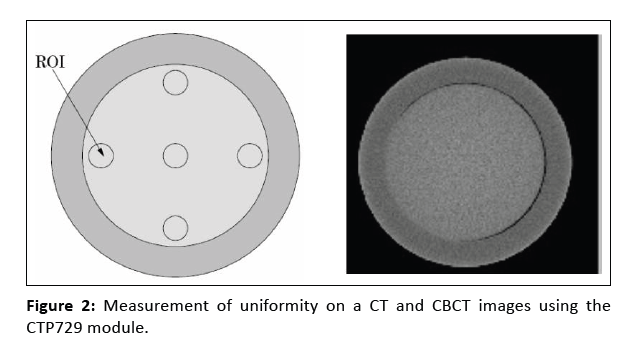

Contrast-to-Noise Ratio

The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) is an essential quantitative measure for evaluating image noise. In Imaging modalities, such as CT and CBCT, noise greatly impairs the identification of close structures of interest, particu-larly in low-contrast regions.

In this study, the image quality for CT and CBCT was assessed using CNR values. The Catphan module with low- contrast cylinders was used to calculate the CNR [Figure 3]. Specifically, a cylindrical disk with a diameter of 15 mm and a nominal low contrast of 1.0 % was sampled with a region of interest (ROI) of 7 mm × 7 mm centered on the disk. A second ROI of the same size was positioned in a nearby homogeneous area devoid of structures to measure the image noise [14].

The CNR was computed using Pylinac with the following equation:

Figure 3: Catphan 604 – Low-Contrast Module (CTP730). The 1.0% low-contrast ROI is shown in yellow, and the background ROI is shown in red.

where ROI(1%) is the mean Hounsfield units (HU) associated with the ROI of a 15‐mm diameter, low-contrast disk with 1% as the nominal target contrast level. The ROI(bg) is the mean HU of the area defined as the back-ground, and SD(bg) represents the standard deviation of the background.

Results

Impact of slice thickness on image quality

To examine the influence of slice thickness on CT and CBCT images, image quality was evaluated by compar-ing several factors such as low-contrast resolution, Hounsfield unit (HU), modulation transfer function (MTF), noise, and uniformity.

Control of slice thickness and low-contrast visibility in CT and CBCT images

Analysis of CT and CBCT images using Pylinac software revealed minor discrepancies in the order of a few micrometers between the programmed and measured thicknesses. The measured slice thicknesses were consist-ently thinner than the programmed slice thicknesses on CBCT than on CT. Furthermore, low-contrast visibility improved with increasing slice thickness and was significantly lower on CBCT than on CT, regardless of the measured slice thickness [Table 1].

| Slice Thickness (mm) | CT: Measured Thickness (mm) | CBCT: Measured Thickness (mm) | CT: Low-Contrast Visibility | CBCT: Low-Contrast Visibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | 0.983 | 0.977 | 4.24 | 3.48 |

| 3 mm | 2.764 | 2.477 | 6.66 | 6.39 |

| 5 mm | 4.253 | 4.216 | 6.85 | 6.53 |

Table 1: Comparison of Slice Thickness and Low-Contrast Visibility in CT and CBCT images

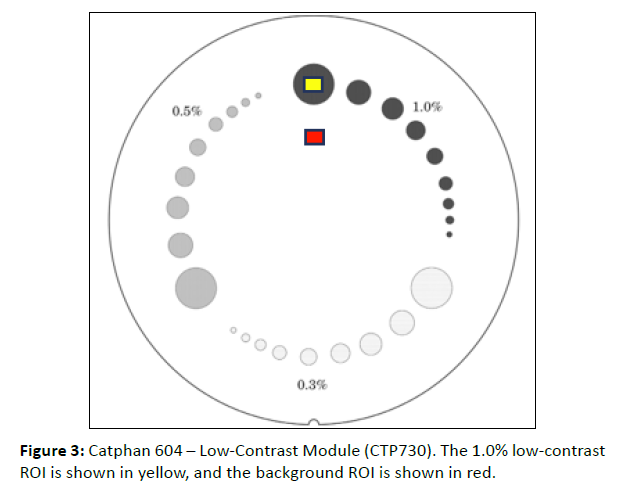

Influence on Hounsfield Units (HU)

[Table 2], presents the average HU values of all the components of the CTP732 module in the Catphan 604 phantom, recommended by the manufacturer for CT images. It should be noted that the manufacturer did not provide specific ranges for CBCT data; the CT ranges were used as a reference to roughly estimate the density variations in the CBCT images.

| Materials | Air | PMP | LDPE | Poly | Acrylic | Bone 20% | Delrin | Bone 50% | Teflon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1046: -986 | -220: -172 | -121: -87 | -65: -29 | 92: 137 | 211: 263 | 344: 387 | 667: 783 | 941: 1060 |

Table 2: Nominal HU for Different Materials given by the manufacturer and used in Catphan 604 phantom

[Figure 4], shows the deviation between the measured HU values and the average values provided by the manu-facturer for each component, depending on the HU of the material. A tolerance of ±40 was adopted to evaluate the HU values.

Figure 4: Difference between HU (given by the manufacturer) and measured HU, for different phantom materials, as a function of nominal HU, for slice thicknesses: 1 mm, 3 mm and 5 mm, in the case of CT and CBCT images.

The HU values obtained from both the CT and CBCT imaging modalities were virtually identical for each part of the phantom and for all slice thicknesses studied. This indicates the low influence of slice thickness on HU for the same modality. However, a notable difference was observed between the HU values obtained by CBCT and CT. In the CT image, the difference increased as the material became denser. This is particularly noticeable for dense materials, such as Teflon and Bone 50%.

CBCT images also revealed a similar pattern, in which the difference generally increased with density. However, the differences were generally smaller, with only the bone 50% exceeding the acceptable limit. Overall, CBCT showed less variability than CT for the slice thicknesses examined in this study.

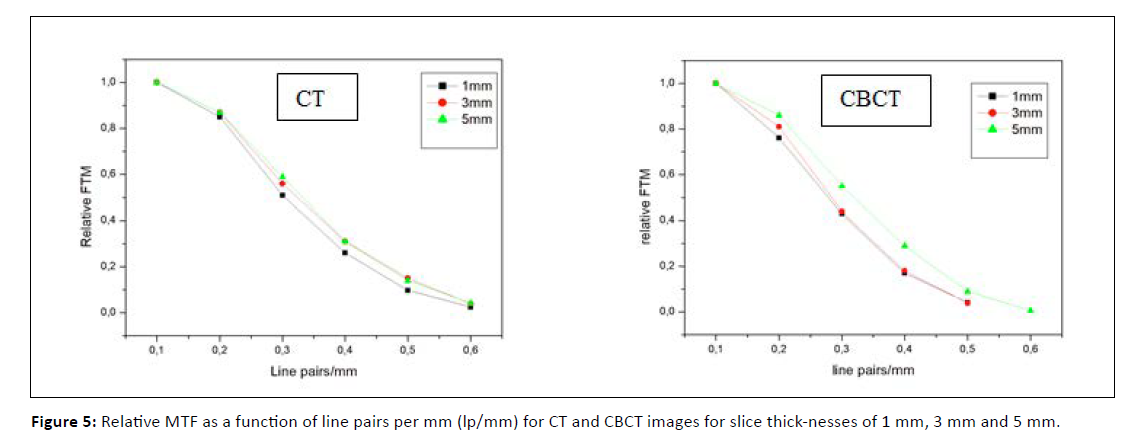

Influence on the MTF

[Figure 5], shows how the Modulation Transfer Function (MTF) changes with increasing line pairs per millimeter (lp/mm) for slice thicknesses of 1, 3, and 5 mm. Although CT and CBCT images follow similar patterns, there are significant differences in their spatial resolutions. The CT images maintained an MTF of up to 6 lp/cm across all slice thicknesses. In contrast, CBCT images only reach up to 5 lp/cm for 1 mm and 3 mm thicknesses. Additionally, the MTF on CBCT decreased more rapidly than that on CT. For both imaging methods, thicker slices provided better resolution than thinner slices. These findings indicate that CT delivers better spatial resolution than CBCT.

Figure 5: Relative MTF as a function of line pairs per mm (lp/mm) for CT and CBCT images for slice thick-nesses of 1 mm, 3 mm and 5 mm.

Influence on the MTF Influence on Noise and Uniformity

[Table 3], shows noise and uniformity index measurements for CT and CBCT images at three slice thicknesses (1 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm). Results indicate that CT images demonstrate excellent homogeneity with minimal distortion. In contrast, CBCT images display more variation, with more significant uniformity differences when changing slice thickness from 1 mm to 3 mm. Noise levels are lower in CT images compared to CBCT.

| Slice Thickness (mm) | Imaging Modality | Average Noise Power | Uniformity Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | CT CBCT |

0.214 0.316 |

0.099 1.787 |

| 3 mm | CT CBCT |

0.235 0.249 |

-0.197 1.896 |

| 5 mm | CT CBCT |

0.232 0.304 |

-0.296 1.900 |

Table 3: Noise and uniformity index value on HU for CT and CBCT images

Influence on the Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR)

In this study, the effect of slice thickness on contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) was evaluated using both CT and CBCT imaging. The CNR was calculated with Pylinac for a low- contrast insert using a 7 mm × 7 mm ROI, with a background region placed directly beneath the insert. Slice thicknesses of 1, 3, and 5 mm were analyzed for each modality.

Referring to [Table 4], the outcomes indicate a notable positive relationship between slice thickness and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) in both CT and CBCT modalities. The CNR values for both imaging techniques improved as the slice thickness increased from 1 mm to 5 mm, owing to decreased image noise resulting from enhanced volume averaging.

| Slice Thickness (mm) | Imaging Modality | CNR |

|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | CT CBCT |

1.06 1.04 |

| 3 mm | CT CBCT |

1.67 1.99 |

| 5 mm | CT CBCT |

2.24 2.17 |

Table 4: CNR Values for CT and CBCT at Different Slice Thicknesses

In the case of CT, the CNR increased from 1.06 at 1 mm to 2.24 at 5 mm, reflecting considerable and stable improvement in low-contrast detectability. On CBCT, the CNR increased from 1.04 at 1 mm to 2.17 at 5 mm, but this enhancement was less pronounced. Interestingly, CBCT provided a slightly higher CNR than CT at 3 mm (1.99 vs. 1.67), although CT consistently had better results than CBCT at 1 mm and 5 mm slices.

These results support the conclusion that CNR improves with higher slice thickness, especially in CT, which performs better than CBCT for low-contrast detection at any slice thickness.

Impact of Slice Thickness on Dose Calculation in CT and CBCT

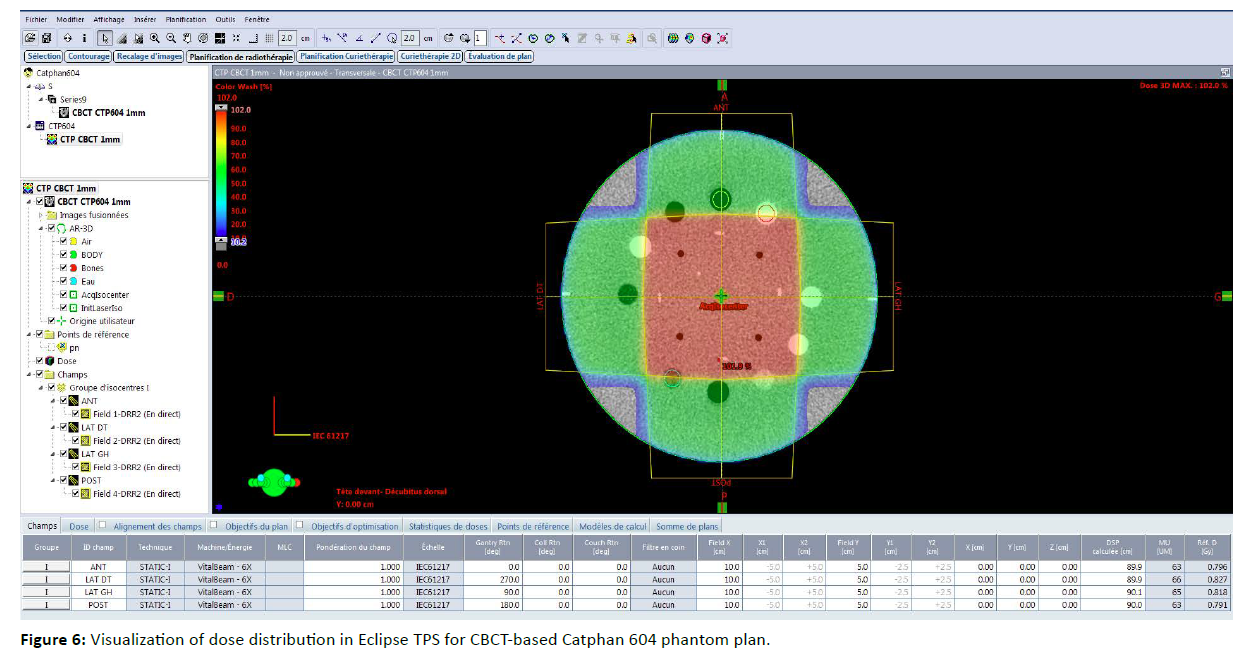

This section presents a comparative study of dose calculations performed in the Eclipse Treatment Planning System (TPS) using CT and CBCT images of the Catphan 604 phantom with varying slice thicknesses. The comparison was based on Dose-Volume Histograms (DVHs). To ensure consistency across DVH comparisons, the same contours were applied to each structure and for all studied slice thicknesses. The structures contoured in this study were the air, bone, and water. The slice thicknesses examined were 1, 3, and 5 mm. The RT plan consisted of four equally weighted box fields with beam energy of 6 MV [Figure 6].

Figure 6: Visualization of dose distribution in Eclipse TPS for CBCT-based Catphan 604 phantom plan.

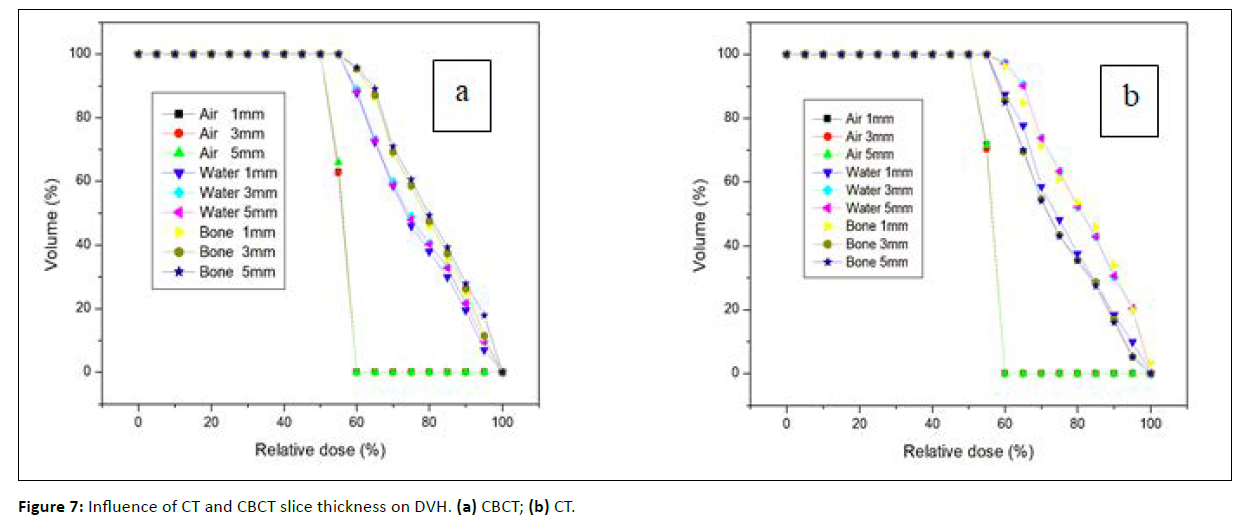

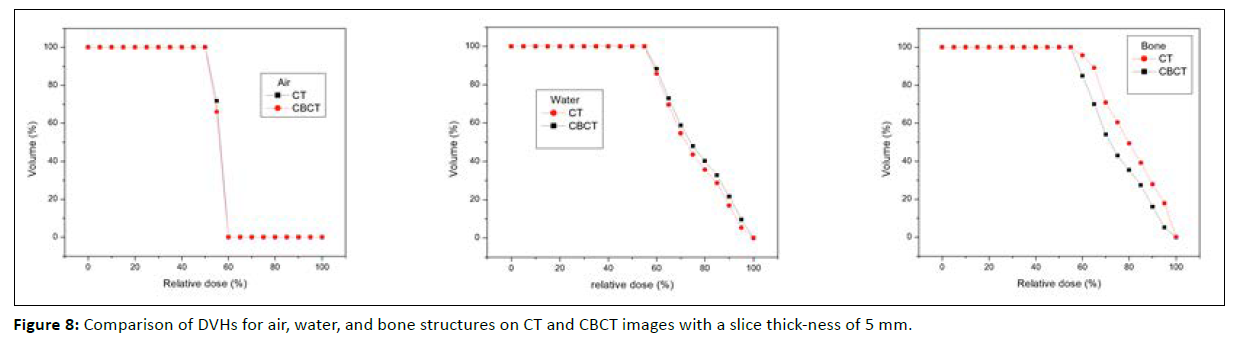

Analysis of the RT plan conducted on both CBCT and CT images indicated that slice thickness had a minimal impact on dose distribution across all examined structures [Figure 7]. A comparative dosimetric evaluation between CT and CBCT imaging was performed through dose-volume histogram (DVH) analysis of the various structures, with a 5 mm slice thickness selected for this investigation [Figure 8].

Figure 7: Influence of CT and CBCT slice thickness on DVH. (a) CBCT; (b) CT.

Figure 8: Comparison of DVHs for air, water, and bone structures on CT and CBCT images with a slice thick-ness of 5 mm.

Based on the obtained results, the DVH corresponding to air demonstrated perfect agreement, indicating that the imaging modality had no effect on dose deposition within the air structures. For water, a minor discrepancy existed between the CT and CBCT DVH curves, with CT exhibiting higher dose values. In the case of the bone, a more pronounced difference was observed between the two modalities.

Discussion

This study highlights the significant influence of slice thickness on image quality parameters in computed to-mography (CT) and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and its effect on RT dose calculation plans. These results corroborate the findings of Chadwick et al. (2010) [15]. This study also aligns with the findings of Prabhakar et al. (2009) [16]. Our observations regarding the impact of slice thickness on spatial resolution and noise levels are consistent with the results of Gaillandre et al. (2023) and McCollough et al. (2024) [17, 18]. These findings are also consistent with Diwakar and Kumar (2018) and Cruz-Bastida et al. (2019) [19, 20]. The superiority of CT over CBCT is consistent with Ronkainen et al. (2022) and Tran et al. (2021) [21, 22]. The limitations of CBCT are consistent with Sajja et al. (2020) and Bryce-Atkinson et al. (2021) [23, 24].

Technological advances in CBCT, such as iterative reconstruction algorithms and deep learning-based de-noising, bridge the performance gap with CT as suggested by Washio et al. (2020) and Kim et al. (2023) [25, 26]. Future research should explore patient-specific factors influencing optimal slice thickness selection as highlighted by Estak et al. (2021) [27].

Conclusion

Our results indicate that slice thickness has a more significant impact on the overall image quality for CT and CBCT, where CT continuously achieved better spatial resolution and Hounsfield Unit accuracy.

Statements & Declarations

Authorship Statement All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding the authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received.

Competing Interests The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author Contributions all authors contributed to the study conception and design.

Ethics Approval Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Consent to Participate not applicable.

Consent to Publish Not applicable.

Data Availability the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Davis AT, Palmer AL, Nisbet A. Can CT scan protocols used for radiotherapy treatment planning be adjusted to optimize image quality and patient dose? A systematic review. The British journal of radiology. 2017; 90: 20160406.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Thorwarth D. Functional imaging for radiotherapy treatment planning: current status and future directions-a review. The British journal of radiology. 2015; 88: 20150056.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Zaffino P, Raggio CB, Thummerer A, Marmitt GG, Langendijk JA et al. Toward Closing the Loop in Image-to-Image Conversion in Radiotherapy: A Quality Control Tool to Predict Synthetic Computed Tomography Hounsfield Unit Accuracy. Journal of Imaging. 2024; 10: 316.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Grégoire V, Guckenberger M, Haustermans K, Lagendijk JJ, Ménard C, et al. Image guidance in radiation therapy for better cure of cancer. Molecular oncology. 2020; 14: 1470-1491.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Issa J, Riad A, Olszewski R, Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska M. The Influence of Slice Thickness, Sharpness, and Contrast Adjustments on Inferior Alveolar Canal Segmentation on Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Scans: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13: 1518.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Lee JH. Comparison of thin-slice CT and conventional CT for lung cancer detection. The American Journal of Radiology. 2015; 204: 637-643.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH. Evaluation of noise and image quality in CT with different slice thicknesses. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics. 2017; 18: 55-63.

- Wang X. Effect of slice thickness on image quality in CT. Journal of Medical Imaging and Health Informatics. 2018; 8: 1057-1062.

- Purdy JA, Smith AR. Three-dimensional Photon Treatment Planning: Report of the Collaborative Working Group on the Evaluation of Treatment Planning for External Photon Beam Radiotherapy. Pergamon Press. 1991.

- Ezzell GA, Galvin JM, Low D, Palta JR, Rosen I, et al. Guidance document on delivery, treatment planning, and clinical implementation of IMRT: report of the IMRT Subcommittee of the AAPM Radiation Therapy Committee. Medical physics 2003; 30: 2089-2115.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Halvorsen PH, Cirino E, Das IJ, Garrett JA, Yang J, et al. AAPM‐RSS medical physics practice guideline 9. a. for SRS‐SBRT. Journal of applied clinical medical physics. 2017; 18: 10-21.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5367b059e4b05a1adcd295c2/t/5efe3c9cb415005eed8ae334/1593719971234/CTP604Manual20200701.pdf

- Kerns JR. Pylinac: Image analysis for routine quality assurance in radiotherapy. Journal of Open Source Software. 2023; 8: 6001.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Wu RY, Liu AY, Williamson TD, Yang J, Wisdom PG, et al. Quantifying the accuracy of deformable image registration for cone‐beam computed tomography with a physical phantom. Journal of applied clinical medical physics. 2019; 20: 92-100.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Chadwick JW, Lam EW. The effects of slice thickness and interslice interval on reconstructed cone beam computed tomographic images. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2010; 110: e37-e42.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Prabhakar R, Ganesh T, Rath GK, Julka PK, Sridhar PS, et al. Impact of different CT slice thickness on clinical target volume for 3D conformal radiation therapy. Medical dosimetry. 2009; 34: 36-41.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Gaillandre Y, Duhamel A, Flohr T, Faivre JB, Khung S, et al. Ultra-high resolution CT imaging of interstitial lung disease: impact of photon-counting CT in 112 patients. European Radiology. 2023; 33: 5528-5539.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- McCollough CH, Winfree TN, Melka EF, Rajendran K, Carter RE, et al. Photon-Counting Detector Computed Tomography Versus Energy-Integrating Detector Computed Tomography for Coronary Artery Calcium Quantitation. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2024; 48: 212-216.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Diwakar M, Kumar M. A review on CT image noise and its denoising. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 2018; 42: 73-88.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Cruz‐Bastida JP, Zhang R, Gomez‐Cardona D, Hayes J, Li K, et al. Impact of noise reduction schemes on quantitative accuracy of CT numbers. Medical Physics. 2019; 46: 3013-3024.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Ronkainen AP, Al-Gburi A, Liimatainen T, Matikka H. A dose–neutral image quality comparison of different CBCT and CT systems using paranasal sinus imaging protocols and phantoms. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2022; 279: 4407-4414.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Tran TTN, Jin DSC, Shih KL, Hsu ML, Chen JC. An image quality comparison study between homemade and commercial dental cone-beam CT systems. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering. 2021; 41: 870-880.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Sajja S, Lee Y, Eriksson M, Nordström H, Sahgal A, et al. Technical principles of dual-energy cone beam computed tomography and clinical applications for radiation therapy. Advances in radiation oncology. 2020; 5: 1-16.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Bryce-Atkinson A, De Jong R, Marchant T, Whitfield G, Aznar MC, et al. Low dose cone beam CT for paediatric image-guided radiotherapy: Image quality and practical recommendations. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2021; 163: 68-75.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Washio H, Ohira S, Funama Y, Morimoto M, Wada K, et al. Metal artifact reduction using iterative CBCT reconstruction algorithm for head and neck radiation therapy: a phantom and clinical study. European Journal of Radiology. 2020; 132: 109293.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Kim K, Lim CY, Shin J, Chung MJ, Jung YG. Enhanced artificial intelligence-based diagnosis using CBCT with internal denoising: Clinical validation for discrimination of fungal ball, sinusitis, and normal cases in the maxillary sinus. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2023; 240: 107708.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Estak K, Mohammadzadeh M, Gharehaghaji N, Mortezazadeh T, Khatyal R, et al. Optimisation of CT scan parameters to increase the accuracy of gross tumour volume identification in brain radiotherapy. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice. 2021; 20: 340-344.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]