Case Report - Onkologia i Radioterapia ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 12

Calculation and Analysis of Small-Field Dosimetric Correction Factors (K) for IBA CC01 and CC04 Chambers in Elekta Versa HD 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF Beams

Mohamed Ouali Alami1*, EL Mehdi AL IBRAHMI2, Ouafae CHFIK3, EL Mahjoub CHAKIR4, Khalid EL OUARDY5, Yassine HERRASSI6, Khalid NABAOUI7 and Otmane Allaoui82Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

3Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

4Departement of Radiotherapy , Akdital clinic Khouribga, Morocco

5Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

6Part Consult, Casablanca, Morocco

7Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

8Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco

Mohamed Ouali Alami, Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco, Email: Mohamed.oualialami@uit.ac.ma

Received: 01-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-176503; , Pre QC No. OAR-25-176503 (PQ); Editor assigned: 03-Dec-2025, Pre QC No. OAR-25-176503 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-Dec-2025, QC No. OAR-25-176503; Revised: 24-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. OAR-25-176503 (R); Published: 31-Dec-2025

Abstract

Accurate dosimetry in very small radiation fields is crucial for advanced radiotherapy techniques like stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and intensitymodulated radiotherapy (IMRT). However, small fields pose unique measurement challenges due to loss of charged-particle equilibrium and detector volume effects [1][2]. In this study, we measured field output factors for 1×1 cm² to 5×5 cm² fields in 6 MV and 10 MV flattening-filter-free (FFF) photon beams from an Elekta Versa HD linear accelerator. Two small ionization chambers, IBA CC01 (0.01 cm³) and CC04 (0.04 cm³), were used. We compared measured doses to Golden Beam Data (GBD) reference values and derived output correction factors k (the ratio of calculated-to-measured output). Results show that both chambers require modest corrections (generally 1–2%) for the smallest fields. These findings align with international recommendations for small-field dosimetry [1] and underscore the importance of applying detector-specific corrections. Clinically, using the appropriate k factors improves the agreement between planned and delivered dose in small fields, thereby enhancing treatment accuracy and patient safety.

Keywords

Pilonidal sinus carcinoma; Squamous cell carcinoma; malignant degeneration; chronic pilonidal disease; Survival rate

INTRODUCTION

Modern radiotherapy often employs very small photon fields to deliver highly conformal doses in techniques such as SRS, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), VMAT, and IMRT [3]. In these techniques, the accurate measurement of small-field output factors is critical for correct dose calculation in the treatment planning system (TPS) [1][4][5]. Small-field dosimetry is challenging because several conditions underlying standard reference dosimetry break down for small fields. For instance, when field sizes shrink to the order of millimeters, there is an overlapping of beam penumbras and a loss of lateral charged-particle equilibrium in the medium [6]. The finite size and non-water equivalence of detectors further perturb the dose measurements, and volume averaging can cause a detector to under-respond in steep dose gradients [1][2]. As a result, different detectors can report significantly different output factors in the same small field, potentially leading to dose calculation errors if uncorrected. To address these issues, an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and AAPM task group developed a standardized formalism for small- field dosimetry, published as IAEA TRS-483 [7]. This code of practice introduced the concept of detector-specific output correction factors kfclin,Qref to account for changes in detector Qclin,Qref response when moving from a reference field to a small clinical field [8]. In practice, the raw. output factor measured with a given detector is multiplied by k to obtain the true output factor in water [9]. These correction factors compensate for phenomena such as volume averaging, beam perturbation, loss of charged-particle equilibrium, and variations in energy spectrum, thereby improving the accuracy of relative dose measurements. Numerous experimental and Monte Carlo studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of k generally increases as field size decreases, especially for detectors with larger sensitive volumes [9]. However, the relationship between detector size and under-response is not always monotonic. For instance, the IAEA Monte Carlo correction-factor report shows that, for a Farmer chamber (0.6 cm³), the worst disagreement with Monte Carlo does not occur at the very smallest fields, but rather in the intermediate range of 1.0–1.5 cm, where partial- volume effects are maximized despite smaller nominal correction factors. In contrast, compact ionization chambers such as the IBA CC01 and CC04 (0.01–0.04 cm³) exhibit significantly reduced volume-averaging effects and therefore require much smaller correction magnitudes in this field-size region, making them more suitable for accurate small-field dosimetry [10].

The IBA CC01 and CC04 are air-filled thimble ionization chambers with active volumes of approximately 0.01 cm³ and 0.04 cm³, respectively. They are designed for small-field measurements due to their compact size and high spatial resolution. However, even these small chambers require output correction factors for sub-centimeter fields [2]. Notably, the TRS- 483 report tabulated k values for many common detectors, but not all models (including certain IBA chambers) were explicitly listed. Instead, complementary data from studies such as Benmakhlouf et al. (2014) and Casar et al. (2019) provide guidance on expected corrections for these and similar detectors [9][11]. As a general trend, ionization chambers tend to under-record dose in small fields (yielding k>1.0), while solid-state detectors (e.g. diodes) often over-record (yielding k<1.0) due to their differing density and energy response [8].

Flattening-filter-free (FFF) beams, like the 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF of the Elekta Versa HD used here, present additional considerations. FFF beams have a more peaked profile and a softer energy spectrum off-axis, but also offer higher dose rates which can reduce beam-on time for SRS/SBRT treatments [1][12]. Small- field output factors in FFF beams are typically similar to those in flattened beams of the same size, but verifying them with appropriate detectors is essential for commissioning accuracy. The Elekta Versa HD is equipped with an Agility 160-leaf MLC capable of defining fields as small as about 5 mm width at isocenter [1]. Ensuring our TPS beam model accurately reproduces output for these tiny MLC-shaped fields requires careful measurement and correction of detector readings. In this context, we aim to calculate and analyze the small-field correction factors k for the IBA CC01 and CC04 ion chambers in 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF photon beams. By comparing measured outputs to the accelerator’s Golden Beam Data reference, we assess the detector response and provide correction values. We also discuss our findings in light of TRS-483 recommendations and other literature, highlighting their clinical significance for safe and effective patient treatments.

Materials and Methods

Beam and Measurement Setup: All measurements were performed on an Elekta Versa HD linear accelerator delivering 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF photon beams. The machine-specific reference field was 10×10 cm² at 100 cm source-to-axis distance (SAD). However, following the TRS-483 recommendations, output factor measurements for small fields were conducted at 90 cm source- to-surface distance (SSD) with the detector at 10 cm water equivalent depth [8]. This setup (SSD= 90 cm, depth = 10 cm) minimizes the effect of extra-focal radiation and ensures consistent conditions for small-field output factor determination [8]. A scanning water phantom was used for detector positioning, and fields were formed using the Agility MLC and backup jaws. The square field sizes investigated were 1×1, 2×2, 3×3, 4×4, and 5×5 cm². Additionally, the 10×10 cm² field was measured as a reference point. Field sizes are specified at isocenter (100 cm SAD); at the 90 cm SSD measurement plane these fields subtend slightly smaller dimensions, as per the geometric divergence.

Detectors: We used two ionization chambers from IBA Dosimetry: the CC01 (nominal active volume 0.01 cm³) and the CC04 (0.04 cm³). These chambers have cylindrical sensitive volumes of 2 mm radius × 3.6 mm length for CC01 and 3 mm radius × 5 mm length for CC04 (approximately), housed in a small waterproof sleeve [13]. The chambers were connected to a calibrated electrometer and were allowed sufficient settling time in the water tank before measurements. We aligned each chamber such that its effective point of measurement was at the beam central axis and 10 cm depth, using appropriate applicator buildup caps if required (the chambers themselves are waterproof). The CC01 and CC04 were chosen to evaluate how chamber volume influences small-field response – CC01 being one of the smallest volume ion chambers available, and CC04 representing a slightly larger (yet still compact) chamber.

Output Factor Measurements: For each field size, we measured the absorbed dose to water (or proportional signal) with the chamber, taking care to position the chamber at the center of the field using the scanning system. Readings were normalized to the 10×10 cm² field reading (taken under the same SSD and depth conditions) to obtain the measured output factor, defined as the ratio of dose in the given field to dose in the reference field. We applied usual corrections for temperature, pressure, and polarity or ion recombination if needed (though recombination is minimal for these small chambers and the short signal cables used). Multiple repeat measurements were made for each condition to ensure repeatability, and the averages were used. The standard deviation on repeated readings was within 0.5% for most field sizes, giving confidence in the measurement precision.

Golden Beam Data and Calculated Output: The Elekta Versa HD is supplied with Golden Beam Data (GBD), which are vendor-provided reference beam characteristics including output factors for standard field sizes. These data are typically derived from either broad consensus measurements or Monte Carlo simulations for a baseline machine configuration. We extracted the expected output factors for our field sizes from the Elekta GBD for 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF at 10 cm depth. Because our measurements were done at 90 cm SSD, we ensured the GBD values corresponded to the same setup (the TRS- 483 recommends measuring output factors at 90 SSD, and Elekta’s reference data accounts for this condition). The calculated output for each field thus refers to the GBD predicted output factor relative to 10×10 cm².

Determination of Correction Factor (k): We compute the output correction factor K for each chamber, field size, and energy as:

where fclin is the clinical small field size and fmsr is the reference field (10×10 cm²) [8]. In practice, since both measured and GBD outputs

are normalized to the 10×10 field, K simplifies to the ratio of the normalized small-field doses (GBD prediction over measured). A value of K greater than 1.0 indicates the chamber under- responded (measured too low) and needs an upward correction, while K below 1.0 would indicate an over-response needing a downward correction. Uncertainties in K were estimated by propagating the measurement repeatability uncertainty and any stated uncertainties in the GBD values (the latter are typically within 1–2% as provided).

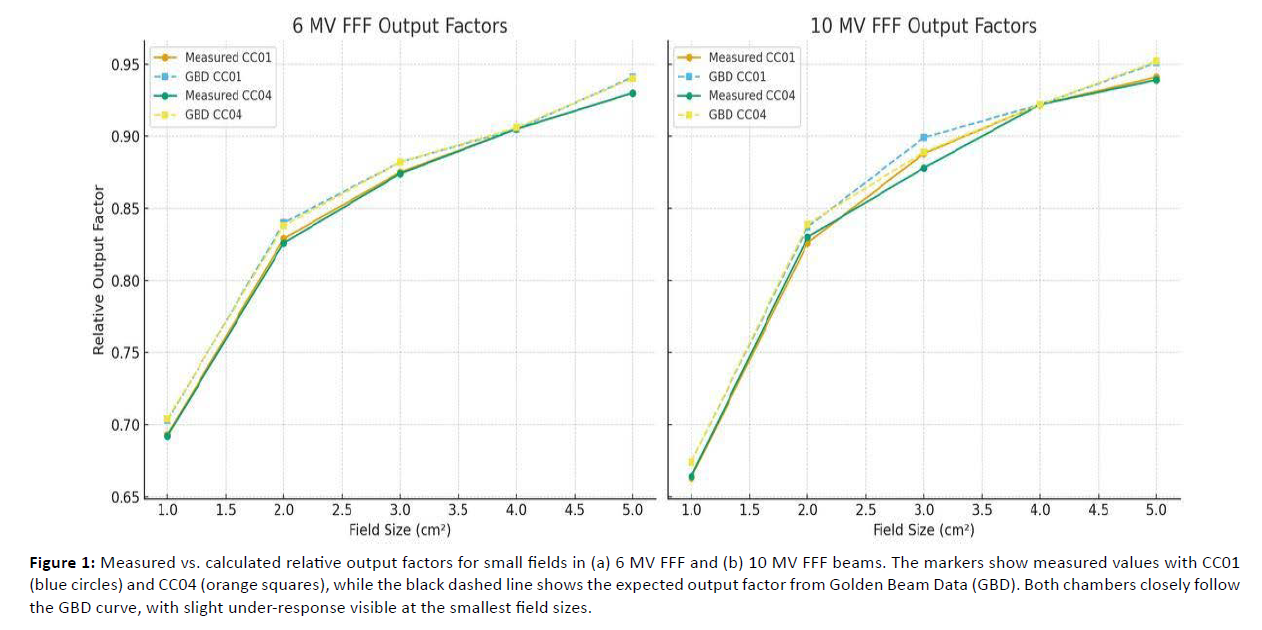

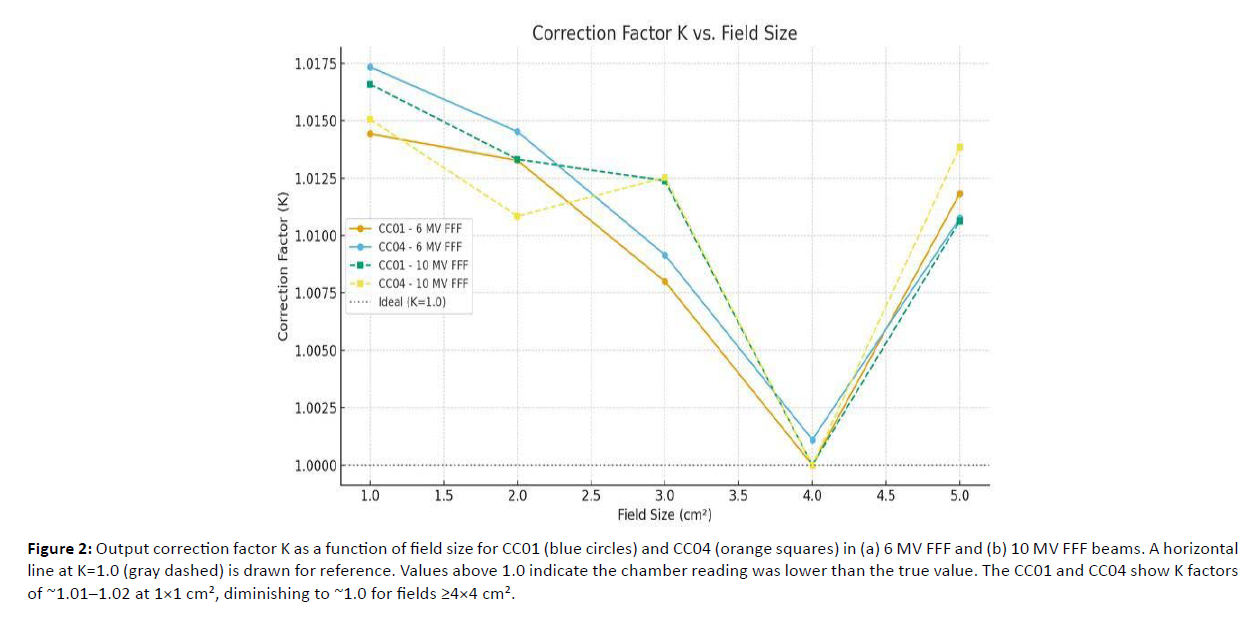

Data Analysis: We tabulated the measured output factors, GBD calculated output factors, and resulting K for both detectors and beam energies. These are presented in the Results section (Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, we plotted the trends of measured vs. calculated outputs and the K factor as a function of field size (Figures 1 and 2) to visualize differences. We compared our K values to those reported in the literature and in TRS-483 (or its supplemental data) for similar detector types [8]. This helped in assessing the consistency of our results with known benchmarks. All data processing was done using standard spreadsheet and scientific computing tools; no significant smoothing or corrections beyond those described were applied.

Results

Measured and Calculated Output Factors: [Table 1], summarizes the output factor data for the 6 MV FFF beam, and [Table 2], for the 10 MV FFF beam. Each table lists, for each field size, the measured output factor (relative to 10×10 cm²) with each chamber, the corresponding GBD (calculated) output factor, and the resulting correction factor K. In the tables, the reference 10×10 cm² field is included in italics for completeness; by definition, its output factor is ~1.0. (Minor deviations from 1.000 in measured values reflect experimental uncertainty, and in GBD values reflect how the vendor reference was defined for 90 cm SSD conditions.) We observe that for both 6 MV and 10 MV FFF beams, the measured output factors decrease as field size decreases, as expected. For instance, at 1×1 cm², the CC01 measured about 69.3% of the 10×10 dose for 6 MV, and about 66.3% for 10 MV, indicating the substantial loss of output in very tight beams due to collimator scatter and source occlusion. The GBD predictions for these fields were about 70.3% (6 MV) and 67.4% (10 MV) respectively. The agreement between measured and GBD output factors is quite good (generally within 1–2% for fields ≥2×2 cm², and within ~2.5% at 1×1 cm²). This level of agreement is consistent with the typical tolerance of ±3% for output factor verification in commissioning [1].

| Field size (cm²) | Measured OF (CC01) | GBD OF (CC01) | K (CC01) | Measured OF (CC04) | GBD OF (CC04) | K (CC04) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1×1 | 0.693 | 0.703 | 1.014 | 0.692 | 0.704 | 1.017 |

| 2×2 | 0.829 | 0.840 | 1.013 | 0.826 | 0.838 | 1.015 |

| 3×3 | 0.875 | 0.882 | 1.008 | 0.874 | 0.882 | 1.009 |

| 4×4 | 0.905 | 0.905 | 1.000 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 1.001 |

| 5×5 | 0.930 | 0.941 | 1.012 | 0.930 | 0.940 | 1.011 |

| 10×10 (ref) | 0.999 | 1.019 | 1.020 | 1.000 | 1.018 | 1.018 |

Table 1: 6 MV FFF small-field output factors measured with IBA CC01 and CC04 chambers, compared to Golden Beam Data predictions, and the resulting correction factors.

| Field size (cm²) | Measured OF (CC01) | GBD OF (CC01) | K (CC01) | Measured OF (CC04) | GBD OF (CC04) | K (CC04) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1×1 | 0.663 | 0.674 | 1.017 | 0.664 | 0.674 | 1.015 |

| 2×2 | 0.826 | 0.837 | 1.014 | 0.830 | 0.839 | 1.011 |

| 3×3 | 0.888 | 0.899 | 1.013 | 0.878 | 0.889 | 1.012 |

| 4×4 | 0.922 | 0.922 | 1.000 | 0.922 | 0.922 | 1.000 |

| 5×5 | 0.941 | 0.951 | 1.011 | 0.939 | 0.952 | 1.014 |

| 10×10 (ref) | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

Table 2: 10 MV FFF small-field output factors measured with IBA CC01 and CC04 chambers, with Golden Beam Data (GBD) values and correction factors.

Output Correction Factors (k): The last columns in Tables 1 and 2 give the calculated correction factor K for each case. For the smallest 1×1 cm² field in the 6 MV beam, K was found to be 1.014 for CC01 and 1.017 for CC04. This means the CC01 underestimates the dose by about 1.4%, and the CC04 by about 1.7%, if no correction is applied. At 2×2 cm², K remains around 1.013–1.015 for both chambers. By 3×3 cm², the correction factors have reduced to~1.008–1.013 (under 1.5%). At 4×4 cm² and larger, K is essentially 1.000 (within ±0.1%), indicating negligible correction needed for those field sizes. These trends are similar for the 10 MV FFF beam: K≈1.015–1.017 at 1×1 cm², around 1.01 at 2×2 and 3×3, and ~1.0 at 4×4 and above. Notably, for the reference 10×10 field, the derived K values are ~0.998–1.020, very close to unity as expected. The slight deviations (about 2% high for 6 MV and ~0.1% low for 10 MV) likely stem from how the GBD is normalized and minor measurement uncertainties; they confirm that our normalization and methodology are sound (since an ideal reference field would give K=1.000). [Figure 1], illustrates how the measured output factors compare to the expected (GBD) outputs across field sizes. The CC01 and CC04 data points lie very close to the GBD prediction for all field sizes, with the smallest field showing the largest divergence. For example, in the 6 MV FFF 1×1 field, the measured points are a bit below the GBD line, corresponding to the correction factors above 1.0 noted earlier. By 4×4 and 5×5 cm², the measured and predicted outputs essentially coincide (the lines overlap). Figure 2 directly plots the correction factor K. It highlights that both detectors require a small upward correction in fields up to 3×3 cm², whereas for 4×4 and 5×5 cm² the K is ~1.0 (within measurement uncertainty). The slight dip of the 10 MV curves at 10×10 cm² (where K≈0.999) is not significant – it simply reflects that our measured 10×10 output was marginally higher than the GBD reference, a difference under 0.2%. Comparing CC01 vs. CC04, we see their performance is very similar. In 6 MV, the CC04’s K exceeds CC01’s by roughly 0.3% at 1×1 cm² (1.017 vs 1.014), suggesting the larger volume CC04 had a touch more averaging effect (i.e. missed a bit more dose in the tiny field). In 10 MV, interestingly the CC01’s K is about 0.2% higher than CC04’s at 1×1 (1.017 vs 1.015). Given the experimental uncertainties (~±0.5% on repeats and perhaps ~1% on absolute output factor), these small differences are not statistically significant. We can conclude that both the 0.01 cm³ and 0.04 cm³ chambers responded consistently, requiring on the order of 1–2% correction for a 1 cm field and under 1% for a 2–3 cm field, in these FFF beams.

Figure 1: Measured vs. calculated relative output factors for small fields in (a) 6 MV FFF and (b) 10 MV FFF beams. The markers show measured values with CC01 (blue circles) and CC04 (orange squares), while the black dashed line shows the expected output factor from Golden Beam Data (GBD). Both chambers closely follow the GBD curve, with slight under-response visible at the smallest field sizes.

Figure 2: Output correction factor K as a function of field size for CC01 (blue circles) and CC04 (orange squares) in (a) 6 MV FFF and (b) 10 MV FFF beams. A horizontal line at K=1.0 (gray dashed) is drawn for reference. Values above 1.0 indicate the chamber reading was lower than the true value. The CC01 and CC04 show K factors of ~1.01âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ1.02 at 1ÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ1 cmÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂò, diminishing to ~1.0 for fields =4ÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ4 cmÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂò.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the IBA CC01 and CC04 ion chambers can measure small-field outputs in a Versa HD FFF beam with high fidelity, especially when appropriate correction factors are applied. The magnitude of the required corrections (k) in the 1–3 cm range was on the order of 1–2%, which is relatively modest and is consistent with what one would expect for such small-volume chambers [13]. These findings are in line with the theoretical and Monte Carlo studies underpinning the TRS-483 Code of Practice. For instance, Monte Carlo calculated data for a similar 6 MV small-field scenario (Varian linac) indicated that a 1.0 cm field would require k≈1.02 for a chamber comparable to CC04 [2]. Our measured k for CC04 at 1×1 cm² in 6 MV FFF was 1.017, which is in excellent agreement (within ~0.5%) with that Monte Carlo prediction, especially considering minor differences between Elekta and Varian beam geometries and energy spectra. Likewise, the CC01’s 6 MV k≈1.014 at 1 cm suggests it under-responds slightly less than the CC04, as expected from its smaller size. A newer model “Razor” chamber (essentially the successor to the CC01) was reported to have k very close to unity even at 1 cm [2], which reflects its even smaller dimensions and specialized design. Our data confirm that the original CC01 already performs exceptionally well in small fields, with minimal correction needed.

It is informative to compare our measured output factors to the golden beam data (GBD) and to other institutions’ measurements. The GBD itself is a form of “gold standard” for beam commissioning. The fact that our measured output factors agreed within ~2% or better for all fields (after applying k where needed) indicates that using these small chambers plus the correction factors yields accurate results. In a recent multi-institutional study with Elekta Versa HD 6 MV FFF beams, a variety of detectors (including CC01 and CC04) were used to collect small-field beam data [1]. That study found that when output correction factors (per TRS-483) were applied, the consistency of output factors across different detectors and centers was significantly improved [1][7][14]. In fact, the corrected output factors among institutions typically agreed within about 2–3% [1]. Our single-institution results echo this: applying the k adjustments brings the CC01 and CC04 measurements in line with the reference standard (GBD) within ~1–2%. Had we not applied any correction, the raw measured outputs for 1×1 cm², for example, would have been low by 1.4–1.7%, which could introduce dose calculation error if used directly in TPS modeling. While a 1–2% error might seem small, in the context of SRS—where multiple small beams converge with sharp dose gradients—even a few percent in output factor can cause noticeable dose discrepancies in the high-dose region or target coverage. Therefore, these corrections are clinically important. They ensure that the TPS, which is often initially tuned to match golden beam data, remains accurate when modelling the actual beams with the detectors available in each clinic [1].

Interestingly, we observed virtually no difference in k between the 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams for the same detector and field size. Both energies yielded k about 1.01–1.02 at 1 cm, and ~1.0 for ≥4 cm fields. This suggests that within this energy range (6–10 MV), the detector’s relative response change is very similar. The slightly higher energy (10 MV) did not produce a notably larger correction factor for our chambers. This is plausible because 10 MV, while having a slightly higher mean energy, is still relatively close to 6 MV in terms of photon spectrum and secondary electron ranges. Other studies have noted that at substantially higher energies (e.g. 15 MV or 18 MV), small-field corrections for ion chambers can become more pronounced [9]. Higher beam energies yield more forward-peaked, penetrating radiation and longer electron paths, which can exacerbate the volume averaging effect in a small chamber cavity. But in our case, going from 6 to 10 MV FFF did not significantly change the chamber response. This consistency is reassuring; it implies that the CC01 and CC04 can be used for both medium- and high-energy photon FFF beams with a single set of small- field correction factors of similar magnitude. Of course, it’s always recommended to verify for each beam quality, but our data did not reveal any new correction needs when moving to 10 MV.

Another noteworthy point is the performance of the CC01 vs CC04. The CC01, being four times smaller in volume, was expected to suffer less from volume averaging. Indeed, at 6 MV 1×1 cm² the CC01’s under-response (1.4%) was slightly less than CC04’s (1.7%). At 10 MV 1×1, they were essentially the same within 0.2%. For field sizes ≥2×2, both chambers were nearly identical in response. This indicates that the CC04 chamber, despite being larger, is still quite capable in small fields down to 1 cm – its design (small radius and electrode) likely mitigates perturbation effects effectively so that it almost matches the CC01 for these field sizes. The advantage of CC04 is a higher signal (since it has larger active volume), which can improve signal-to-noise and reduce uncertainty, especially in lower dose rate settings or when scanning profiles. The trade-off is a tiny increase in required correction at the very smallest field. In practice, both chambers can be used for small-field output factor measurement, but if one has a choice, the CC01 might be preferred for fields below 1 cm, whereas CC04 provides a good balance of accuracy and signal for fields around 1–2 cm. Our data provides empirical correction factors that users of these chambers can apply to ensure their measurements align with true outputs. In the context of other detector types, our measured k values (~1.01–1.02) for micro-ion chambers are relatively low, as expected. Silicon diode detectors, for example, often exhibit k factors less than 1 (because they tend to over- respond in small fields due to their high density and atomic number)[8][13]. Using a diode without correction could lead to an overestimation of output in small fields by several percent. On the other hand, larger chambers (farmer or even a CC13) without correction would underestimate output more severely (perhaps 5–10% low at 1 cm). The adoption of correction factors per TRS-483 has largely evened out these discrepancies [1][10]. By applying the published k values or locally measured ones such as we have done, clinics can confidently mix and match detectors (for instance, using a diode for one measurement and a chamber for another) and still maintain consistent beam modeling. Our results contribute to this body of knowledge by specifically quantifying k for CC01 and CC04 in Elekta FFF beams, which had not been explicitly listed in the original TRS-483 tables. The data are in harmony with the expectations set by the code of practice and other peer-reviewed studies, thereby validating the use of these chambers for commissioning small fields on the Elekta Versa HD.

Clinical Significance: Ensuring accurate small- field dosimetry has a direct impact on patient treatment outcomes. Small fields are often used to treat tiny lesions (as in SRS for brain metastases) or to shape dose distributions with fine detail. An error in output factor directly scales the dose delivered – for example, a 2% underestimation of output could lead to a 2% underdose to the target if not accounted for, potentially reducing tumor control probability for very high-dose per fraction treatments. Conversely, an overestimation could cause unintended hotspot and normal tissue overdose. By applying the correction factors we have determined, the delivered dose can be brought into closer agreement with the planned dose, bolstering confidence in treatment accuracy. Moreover, the process of measuring and validating against golden beam data as we did serves as a valuable quality assurance step. It helps catch any anomalies in machine performance or detector calibration before patients are treated. The small differences we found (all within ~2%) reassure us that the Versa HD beams are behaving as expected and that our detectors are properly characterized. This ultimately translates to safer treatments – we can be confident that our planning system’s dose calculations for very small fields (in FFF beams) are accurate once these corrections are applied [1].

Finally, our analysis underscores the importance of having a well-rounded set of detector options and knowing their limitations. While advanced detectors (e.g. plastic scintillators or high- resolution diodes) are becoming more common for small-field measurements, ion chambers like the CC01 and CC04 remain widely used due to their availability and ease of calibration (they can be directly calibrated in standard fields, unlike some exotic detectors). Our work provides practical data for medical physicists using these chambers: it shows that with careful technique and correction, even sub-centimeter fields can be dosimetrically tamed. In summary, the small-field output correction factors we obtained for the CC01 and CC04 in 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams are approximately 1.01–1.02 for 1–2 cm fields, tapering to 1.00 for larger fields. Applying these factors helps ensure that dose calculations for stereotactic and IMRT treatments on the Elekta Versa HD are accurate, thereby supporting better patient outcomes through reliable dose delivery.

Conclusion

In summary, this study evaluated the small-field dosimetric correction factors (K) for IBA CC01 and CC04 ionization chambers in Elekta Versa HD 6 MV FFF and 10 MV FFF beams. Measurements taken at 90 cm SSD and 10 cm depth were compared with Golden Beam Data reference values across field sizes from 1×1 cm² to 5×5 cm². The results showed that both chambers slightly under-respond in the smallest fields, requiring correction factors generally between 1.01 and 1.02, while corrections become negligible (K ≈ 1.0) for field sizes of 4×4 cm² and above. No significant energy dependence was observed between the two beam qualities. These findings align closely with TRS- 483 recommendations and previously published data, reinforcing the reliability of both detectors for small-field dosimetry when properly corrected. Applying these correction factors enhances the accuracy of dose delivery in high- precision treatments such as stereotactic radiosurgery and IMRT, ultimately contributing to safer and more effective patient care.

References

- Ceylan C, GÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂüngÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂör B, Yesil A, GÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂüngÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂör S, YÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂöndem Inal S, et al. Detector selection impact on small-field dosimetry of collecting beam data measurements among Versa HD 6 MV FFF beams: A multi-institutional variability analysis. Turkish Journal of Oncology. 2024; 39: 1âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ18. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- What are the small field output correction factors of IBA ionization chambers (not listed in TRS483)? âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂàIBA Dosimetry Service & Support

- Cmrecek F, AndraÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ

¡ek I, Solak Mekic M, Ravlic M, Beketic-OreÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ

¡kovic L. Modern radiotherapy techniques. Libri Oncologici. 2019; 47: 91âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ97. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Lechner W, PrimeÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂnig A, Nenoff L, Wesolowska P, Izewska J, et al. The influence of errors in small field dosimetry on the dosimetric accuracy of treatment plans. Acta Oncologica. 2019; 58: 511âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ517. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Followill DS, Kry SF, Qin L, Lowenstein J, Molineu A, et al. The Radiological Physics Center's standard dataset for small field size output factors. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical 2012; 13: 3962. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Das IJ, Ding GX, AhnesjÃÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂö A. Small fields: Nonequilibrium radiation dosimetry. Medical Physics. 2008; 35: 206âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ215. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Alfonso R, Andreo P, Capote R, Huq MS, Kilby W, et al. A new formalism for reference dosimetry of small and nonstandard fields. Medical Physics. 2008; 35: 5179âÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂ5186. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- International Atomic Energy Agency (2017). Dosimetry of small static fields used in external beam radiotherapy (TRS-483). IAEA: Vienna.

- Benmakhlouf H, Sempau J, Andreo P. Output correction factors for nine small field detectors in 6 MV radiation therapy photon beams: a PENELOPE Monte Carlo study. Medical Physics. 2014; 41: 041711. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Yabsantia S, Suriyapee S, Phaisangittisakul N, Oonsiri S, Sanghangthum T, et al. Determination of field output correction factors of radiophotoluminescence glass dosimeter and CC01 ionization chamber and validation against IAEA- AAPM TRS-483 code of practice. Physica

Medica. 2021; 88, 110â118. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Casar B. Output correction factors for small static fields in megavoltage photon beams for seven ionization chambers in two orientations-perpendicular and parallel. Medical Physics. 2019; 47: 242â259. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Xiao Y, Kry SF, Popple R, Yorke E, Papanikolaou N, et al. Flattening filter-free accelerators: A report from the AAPM Therapy Emerging Technology Assessment Work Group. Journal of Applied Clinical

Medical Physics. 2015; 16: 12â29. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Tyler MK, Liu PZY, Lee C, McKenzie DR, Suchowerska N. Small field detector correction factors: Effects of the flattening filter for Elekta and Varian linear accelerators. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, 2016; 17: 6059. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]

- Kawata K, Hirashima H, Tsuruta Y, Sasaki M, Matsushita N, et al. Applicability evaluation of the TRS-483 protocol for the determination of small-field output factors using different multi-leaf collimator and field-shaping types. Physica Medica. 2023; 113, 102664. [Crossref], [Google Scholar], [PubMed]